An exile that turns into a homeland

Sudanese-Armenian cultural heritage, as part of Sudan’s broader, diverse cultural heritage, faces the threat of erasure. Previous limited attempts to document this community were small in scope, primarily academic and have made no material results accessible for Sudanese or Armenians.

/ answered

Sudanahye: the Sudanese-Armenian Heritage Project

Sudanese-Armenian cultural heritage, as part of Sudan’s broader, diverse cultural heritage, faces the threat of erasure. Previous limited attempts to document this community were small in scope, primarily academic and have made no material results accessible for Sudanese or Armenians.

It was within this context that the sudanahye (meaning Sudanese-Armenian in Armenian) project was conceived with the aim of creating an enduring legacy for this community via the development of an archive of Sudanese-Armenian history. What began as a personal effort to interview Sudanese-Armenians, has, with the support of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, grown into a multimedia project that seeks to document history, preserve heritage and re-imagine the community today by linking younger generations to their oral histories and archives.

The project’s director, Vahe Boghosian, is of Sudanese-Armenian origin and although he has never visited Sudan, he found the opportunity to work with like-minded Sudanese and Egyptians to set up a team when he moved to Cairo, where large Sudanese communities migrated following the war. His participation in numerous events related to culture, history, art and family archives in Cairo played a key role in integrating him into the Sudanese community. Throughout this period, he gained a deeper understanding of Sudanese culture, society and values.

As a result of these efforts, Sudanahye is piecing together stories of a community that were almost lost to time - stories that harness memories of a more pluralist past to help imagine a more co-existent future for Sudan.

On the banks of the Nile, a place of exile becomes a homeland

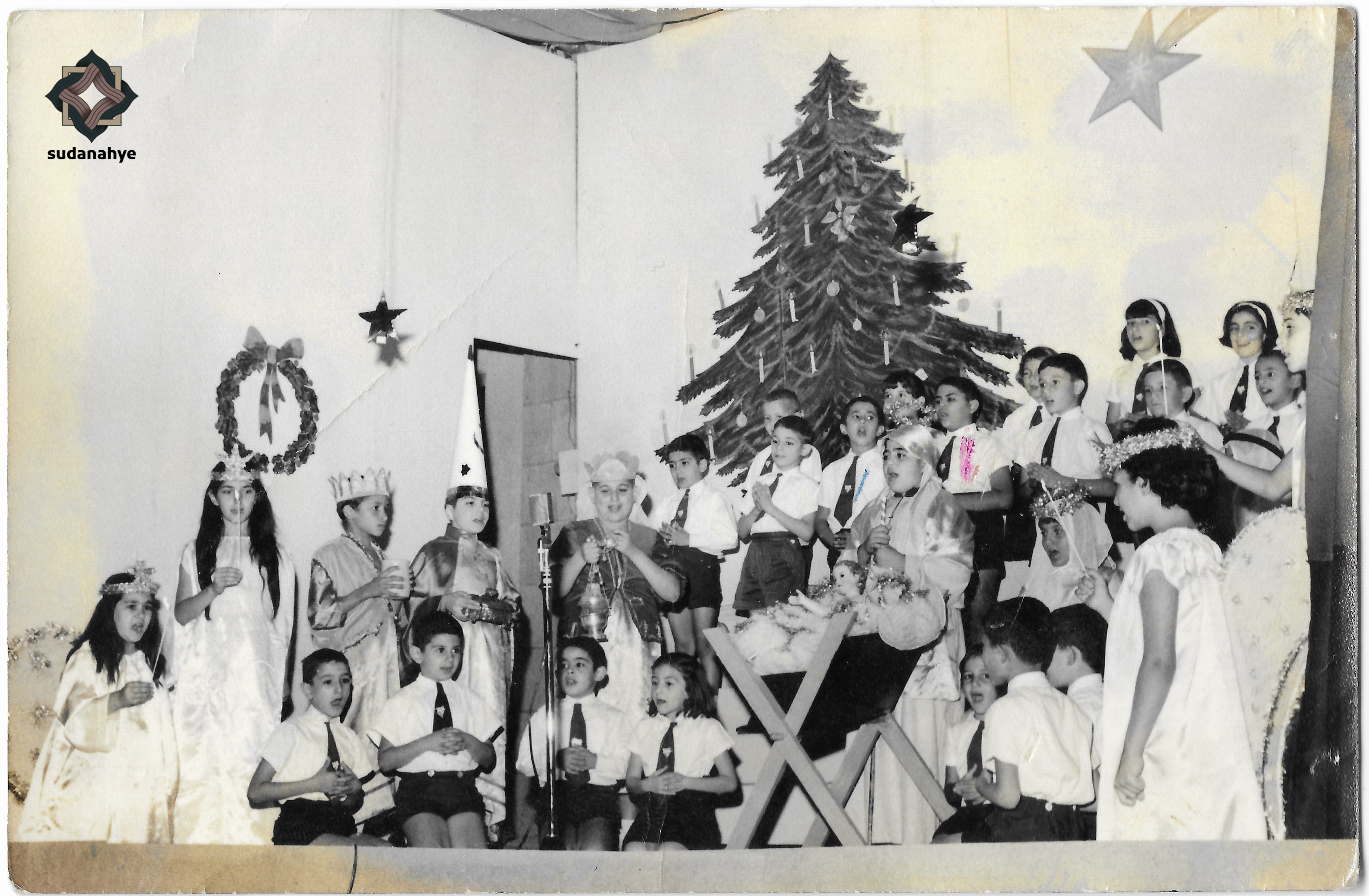

For so many Sudanese-Armenians, photos and stories about the long history of their life in Sudan were all they possessed to pass down to the next generation. They represented a real window onto the interaction of Armenian culture with the various aspects of Sudan’s diverse culture in all walks of life. The photos often show children at the Armenian school or portray a vibrant social scene at the Armenian Club, family picnics at Jebel Awliya or boat trips on the Nile - stories of belonging and co-existence.

Photos are usually taken to document happy times and as such, we find that most of these images and stories do not cover the history of exile, loss or deprivation suffered by Sudanese-Armenians. Unfortunately, when the war erupted in 2023, they were forced to relive a similar history which resulted in the loss of homes and lives including the death in their home in Khartoum of two cherished members of the community, the sisters Zvart and Arpi Yegavian. It is therefore necessary to document and preserve what remains and to establish a lasting heritage to ensure that their heritage, and that of their community is not lost.

Armenian migration from Arabkir to Sudan

The Yegavian sisters were descendants of Karnig Yegavian, an Armenian from Arabkir (a historic town in the Armenian Highlands which was later annexed by the Ottoman Empire and today forms part of eastern Turkey). Karnig survived the 1915 Armenian Genocide and migrated to Sudan in 1923 where other Arabkir Armenians had already established themselves. A small number of Armenians from Arabkir and elsewhere had come to Sudan after the British conquest in 1899, mostly as an extension of trade networks from Egypt, with the hope of gaining wealth and supporting relatives in the homeland.

These early pioneers established a Sudan branch of the global Armenian charity AGBU (Armenian General Benevolent Union). Through the records of AGBU Sudan, preserved at the archives of AGBU in Cairo, we know that the early community came together to raise funds for compatriots in the Armenian Highlands who faced massacres, poverty, and eventually in 1915, Genocide at the hands of the Ottoman Empire.

Many of these Armenian men in Sudan, having lost their own families during the Genocide, responded to appeals from orphanages in Syria and Lebanon where many survivors had found refuge. Others, through much hardship, brought their surviving family members to Sudan. By the 1930s, a small group of Armenian traders had grown into a network of families spread across Sudan, from Atbara to Malakal and from Kassala to Al-Fashir, with the heart of the community in Khartoum.

Building a vibrant community in Sudan

Their fluency in Arabic and English meant Armenians had an advantage in the job market and that they were respected and accepted by Sudanese society as well as by the governing British authorities. In this way, Karnig Yegavian found employment as an accountant at the National Bank of Egypt’s branch in Khartoum. Armenians, like the Greeks, Syrians, Jews and Italians, occupied a middle-ground in Sudan: adjacent to colonial power, but also working and living closely with Sudanese society. The dynamic of this relationship is further demonstrated by Andon Kazandjian, the Armenian photographer at Gordon Studios, the official photographers for the British authorities. The legacy of Armenian photographers like Kazandjian likely explains why so many photographs documenting the life of Armenians in Sudan have survived. While some like Andon provided services for the British, the majority of Armenians became traders, particularly as local dealers for Western companies or by establishing factories and industries. Karnig’s relative, Nerses Yegavian for example, worked for S & S Vanian, a department store in Khartoum known colloquially as the ‘Harrods of Africa’.

By the time Sudan gained independence in 1956, Armenians were a well-established and respected minority whose life, as a Christian “khawaja” community, revolved around the Armenian Church, Club, and School. After independence, members of the community became Sudanese citizens. At the time, Armenia was still part of the Soviet Union which meant, unlike other minorities, Armenians in Sudan had no original homelands to return to. Nevertheless, they were able to preserve their identity while living in Sudan through their faith, culture and family - whether through the church in Khartoum, an Armenian school in Gedaref, or in an Armenian home in Malakal.

The journey to decline

The Armenian community’s life was significantly disrupted in the late 1960s and 1970s when nationalisation policies were targeted against foreign businesses and individuals. Some Armenians left preemptively but others were forced to flee as result of the persecution. However, a number of Armenians preferred to remain and weather the political upheavals of the following decades while continuing to centre their community life around Armenian institutions in Khartoum.

As the political situation in the 1980s and onwards deteriorated, the community continued to shrink in size and the Armenian school eventually closed down due to a lack of students. The once-vibrant Armenian Club, often known as the place to be for Khartoum’s upper classes with its soirees and sporting events, was taken over by the authorities. In recent decades, the church remained the only community hub, serving approximately 50 Armenians in the 2000s, down from approximately 1,000 in the 1960s.

The Armenian Church stands to this day but like much of Khartoum, it now bears the scars of war and like millions of Sudanese, the remaining Sudanese-Armenians have also sought refuge outside the country. This departure marks an end to a community of over a hundred years and a legacy that saw Armenians co-exist with Sudanese to advance economy, pioneer industry and give birth to prominent achievers such as Zarouhi Sarkissian (Sudan’s first female doctor graduating in 1952 along with Khalda Zahir) or Jack Iskhanes (who advanced a unique Sudanese style of architecture). Whether Armenians will return, and what they will return to, remains to be seen. Yet, despite the political turmoil, many Sudanese-Armenians will proudly declare ‘Ana Sudani’, I am Sudanese, as they continue to be respected and welcomed in Sudanese society.

Cover picture: The Armenian School © Sudanahye picture archive

Sudanahye: the Sudanese-Armenian Heritage Project

Sudanese-Armenian cultural heritage, as part of Sudan’s broader, diverse cultural heritage, faces the threat of erasure. Previous limited attempts to document this community were small in scope, primarily academic and have made no material results accessible for Sudanese or Armenians.

It was within this context that the sudanahye (meaning Sudanese-Armenian in Armenian) project was conceived with the aim of creating an enduring legacy for this community via the development of an archive of Sudanese-Armenian history. What began as a personal effort to interview Sudanese-Armenians, has, with the support of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, grown into a multimedia project that seeks to document history, preserve heritage and re-imagine the community today by linking younger generations to their oral histories and archives.

The project’s director, Vahe Boghosian, is of Sudanese-Armenian origin and although he has never visited Sudan, he found the opportunity to work with like-minded Sudanese and Egyptians to set up a team when he moved to Cairo, where large Sudanese communities migrated following the war. His participation in numerous events related to culture, history, art and family archives in Cairo played a key role in integrating him into the Sudanese community. Throughout this period, he gained a deeper understanding of Sudanese culture, society and values.

As a result of these efforts, Sudanahye is piecing together stories of a community that were almost lost to time - stories that harness memories of a more pluralist past to help imagine a more co-existent future for Sudan.

On the banks of the Nile, a place of exile becomes a homeland

For so many Sudanese-Armenians, photos and stories about the long history of their life in Sudan were all they possessed to pass down to the next generation. They represented a real window onto the interaction of Armenian culture with the various aspects of Sudan’s diverse culture in all walks of life. The photos often show children at the Armenian school or portray a vibrant social scene at the Armenian Club, family picnics at Jebel Awliya or boat trips on the Nile - stories of belonging and co-existence.

Photos are usually taken to document happy times and as such, we find that most of these images and stories do not cover the history of exile, loss or deprivation suffered by Sudanese-Armenians. Unfortunately, when the war erupted in 2023, they were forced to relive a similar history which resulted in the loss of homes and lives including the death in their home in Khartoum of two cherished members of the community, the sisters Zvart and Arpi Yegavian. It is therefore necessary to document and preserve what remains and to establish a lasting heritage to ensure that their heritage, and that of their community is not lost.

Armenian migration from Arabkir to Sudan

The Yegavian sisters were descendants of Karnig Yegavian, an Armenian from Arabkir (a historic town in the Armenian Highlands which was later annexed by the Ottoman Empire and today forms part of eastern Turkey). Karnig survived the 1915 Armenian Genocide and migrated to Sudan in 1923 where other Arabkir Armenians had already established themselves. A small number of Armenians from Arabkir and elsewhere had come to Sudan after the British conquest in 1899, mostly as an extension of trade networks from Egypt, with the hope of gaining wealth and supporting relatives in the homeland.

These early pioneers established a Sudan branch of the global Armenian charity AGBU (Armenian General Benevolent Union). Through the records of AGBU Sudan, preserved at the archives of AGBU in Cairo, we know that the early community came together to raise funds for compatriots in the Armenian Highlands who faced massacres, poverty, and eventually in 1915, Genocide at the hands of the Ottoman Empire.

Many of these Armenian men in Sudan, having lost their own families during the Genocide, responded to appeals from orphanages in Syria and Lebanon where many survivors had found refuge. Others, through much hardship, brought their surviving family members to Sudan. By the 1930s, a small group of Armenian traders had grown into a network of families spread across Sudan, from Atbara to Malakal and from Kassala to Al-Fashir, with the heart of the community in Khartoum.

Building a vibrant community in Sudan

Their fluency in Arabic and English meant Armenians had an advantage in the job market and that they were respected and accepted by Sudanese society as well as by the governing British authorities. In this way, Karnig Yegavian found employment as an accountant at the National Bank of Egypt’s branch in Khartoum. Armenians, like the Greeks, Syrians, Jews and Italians, occupied a middle-ground in Sudan: adjacent to colonial power, but also working and living closely with Sudanese society. The dynamic of this relationship is further demonstrated by Andon Kazandjian, the Armenian photographer at Gordon Studios, the official photographers for the British authorities. The legacy of Armenian photographers like Kazandjian likely explains why so many photographs documenting the life of Armenians in Sudan have survived. While some like Andon provided services for the British, the majority of Armenians became traders, particularly as local dealers for Western companies or by establishing factories and industries. Karnig’s relative, Nerses Yegavian for example, worked for S & S Vanian, a department store in Khartoum known colloquially as the ‘Harrods of Africa’.

By the time Sudan gained independence in 1956, Armenians were a well-established and respected minority whose life, as a Christian “khawaja” community, revolved around the Armenian Church, Club, and School. After independence, members of the community became Sudanese citizens. At the time, Armenia was still part of the Soviet Union which meant, unlike other minorities, Armenians in Sudan had no original homelands to return to. Nevertheless, they were able to preserve their identity while living in Sudan through their faith, culture and family - whether through the church in Khartoum, an Armenian school in Gedaref, or in an Armenian home in Malakal.

The journey to decline

The Armenian community’s life was significantly disrupted in the late 1960s and 1970s when nationalisation policies were targeted against foreign businesses and individuals. Some Armenians left preemptively but others were forced to flee as result of the persecution. However, a number of Armenians preferred to remain and weather the political upheavals of the following decades while continuing to centre their community life around Armenian institutions in Khartoum.

As the political situation in the 1980s and onwards deteriorated, the community continued to shrink in size and the Armenian school eventually closed down due to a lack of students. The once-vibrant Armenian Club, often known as the place to be for Khartoum’s upper classes with its soirees and sporting events, was taken over by the authorities. In recent decades, the church remained the only community hub, serving approximately 50 Armenians in the 2000s, down from approximately 1,000 in the 1960s.

The Armenian Church stands to this day but like much of Khartoum, it now bears the scars of war and like millions of Sudanese, the remaining Sudanese-Armenians have also sought refuge outside the country. This departure marks an end to a community of over a hundred years and a legacy that saw Armenians co-exist with Sudanese to advance economy, pioneer industry and give birth to prominent achievers such as Zarouhi Sarkissian (Sudan’s first female doctor graduating in 1952 along with Khalda Zahir) or Jack Iskhanes (who advanced a unique Sudanese style of architecture). Whether Armenians will return, and what they will return to, remains to be seen. Yet, despite the political turmoil, many Sudanese-Armenians will proudly declare ‘Ana Sudani’, I am Sudanese, as they continue to be respected and welcomed in Sudanese society.

Cover picture: The Armenian School © Sudanahye picture archive

.svg)