(Dis)Similarities

If you look closer you will discover that the very beauty of our diversity lies in our differences.

An exile that turns into a homeland

An exile that turns into a homeland

Sudanahye: the Sudanese-Armenian Heritage Project

Sudanese-Armenian cultural heritage, as part of Sudan’s broader, diverse cultural heritage, faces the threat of erasure. Previous limited attempts to document this community were small in scope, primarily academic and have made no material results accessible for Sudanese or Armenians.

It was within this context that the sudanahye (meaning Sudanese-Armenian in Armenian) project was conceived with the aim of creating an enduring legacy for this community via the development of an archive of Sudanese-Armenian history. What began as a personal effort to interview Sudanese-Armenians, has, with the support of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, grown into a multimedia project that seeks to document history, preserve heritage and re-imagine the community today by linking younger generations to their oral histories and archives.

The project’s director, Vahe Boghosian, is of Sudanese-Armenian origin and although he has never visited Sudan, he found the opportunity to work with like-minded Sudanese and Egyptians to set up a team when he moved to Cairo, where large Sudanese communities migrated following the war. His participation in numerous events related to culture, history, art and family archives in Cairo played a key role in integrating him into the Sudanese community. Throughout this period, he gained a deeper understanding of Sudanese culture, society and values.

As a result of these efforts, Sudanahye is piecing together stories of a community that were almost lost to time - stories that harness memories of a more pluralist past to help imagine a more co-existent future for Sudan.

On the banks of the Nile, a place of exile becomes a homeland

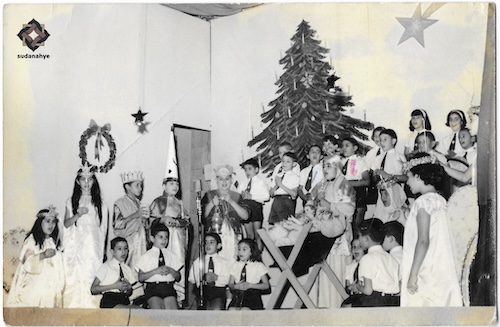

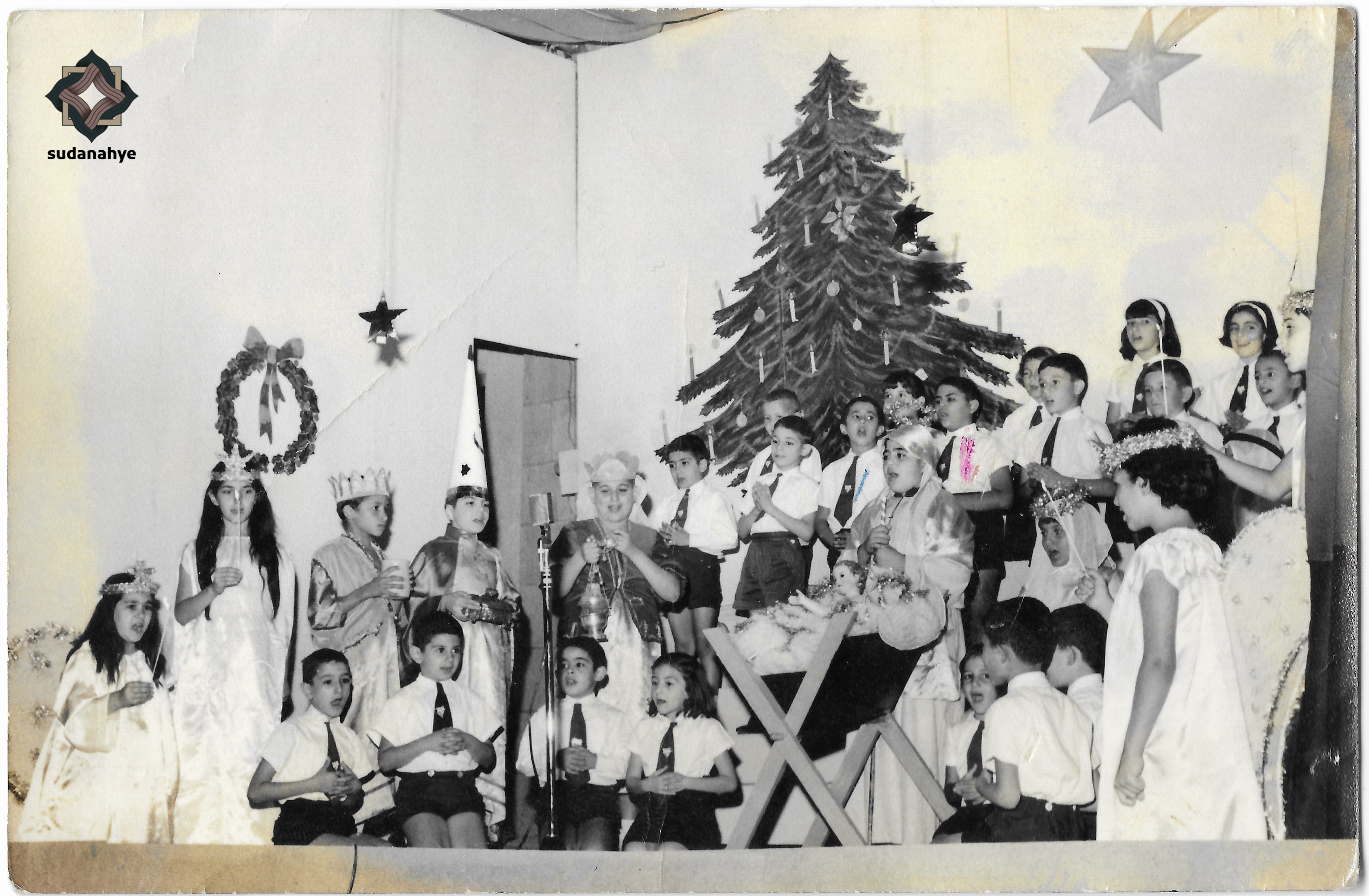

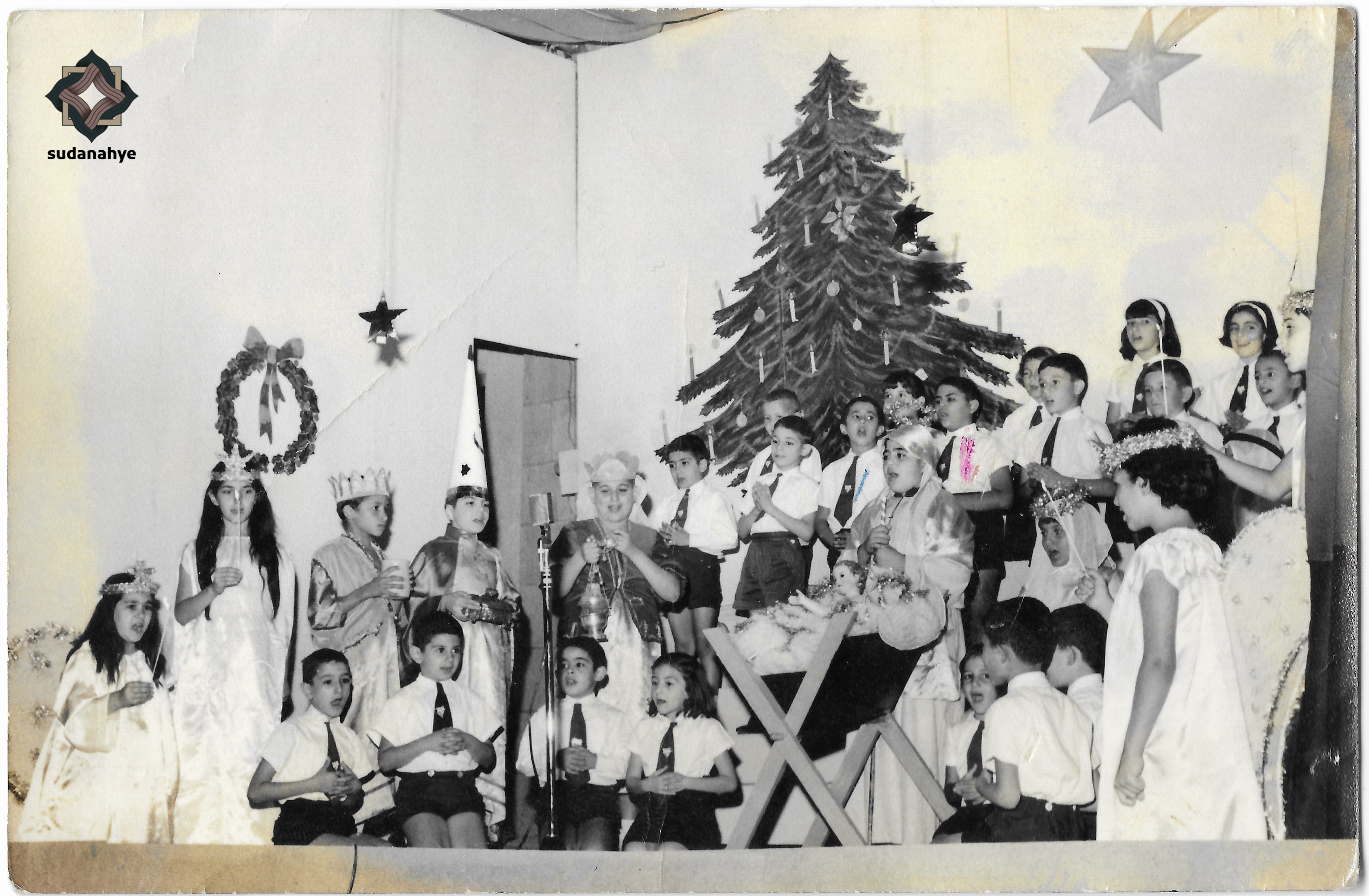

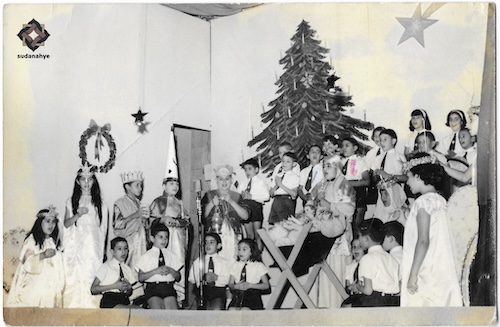

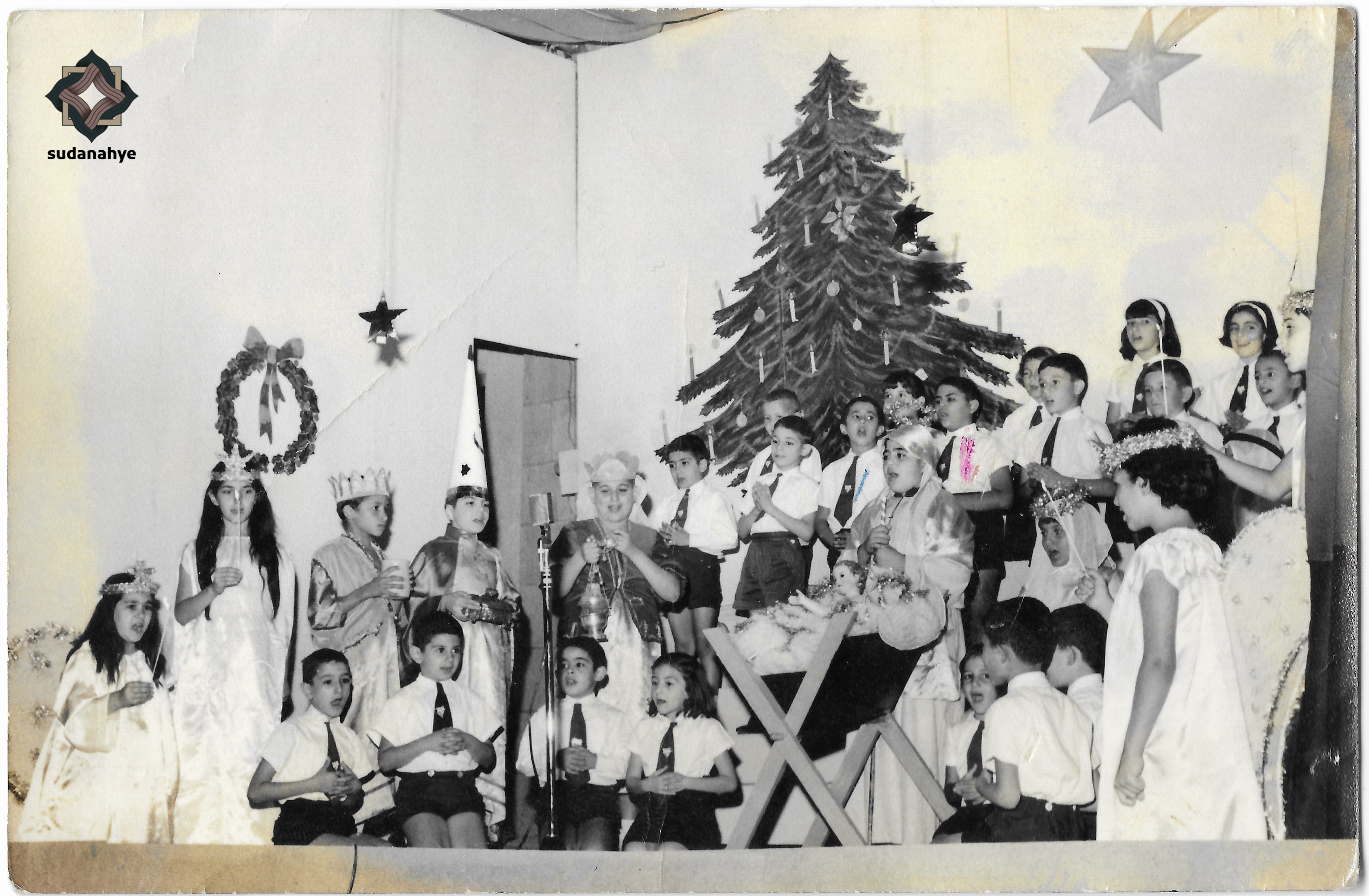

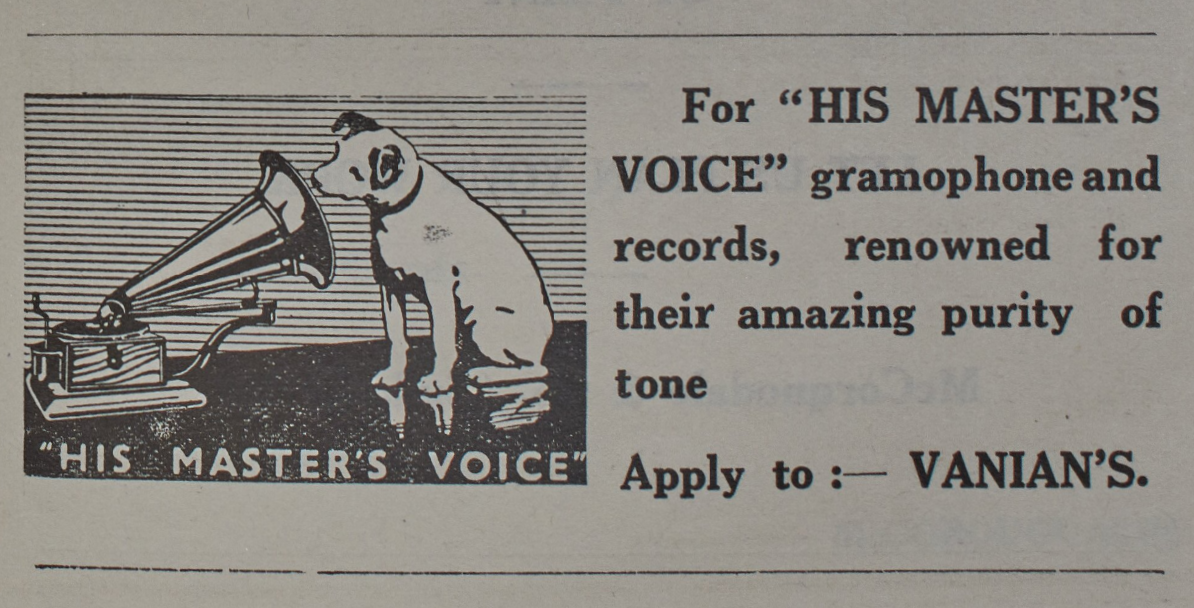

For so many Sudanese-Armenians, photos and stories about the long history of their life in Sudan were all they possessed to pass down to the next generation. They represented a real window onto the interaction of Armenian culture with the various aspects of Sudan’s diverse culture in all walks of life. The photos often show children at the Armenian school or portray a vibrant social scene at the Armenian Club, family picnics at Jebel Awliya or boat trips on the Nile - stories of belonging and co-existence.

Photos are usually taken to document happy times and as such, we find that most of these images and stories do not cover the history of exile, loss or deprivation suffered by Sudanese-Armenians. Unfortunately, when the war erupted in 2023, they were forced to relive a similar history which resulted in the loss of homes and lives including the death in their home in Khartoum of two cherished members of the community, the sisters Zvart and Arpi Yegavian. It is therefore necessary to document and preserve what remains and to establish a lasting heritage to ensure that their heritage, and that of their community is not lost.

Armenian migration from Arabkir to Sudan

The Yegavian sisters were descendants of Karnig Yegavian, an Armenian from Arabkir (a historic town in the Armenian Highlands which was later annexed by the Ottoman Empire and today forms part of eastern Turkey). Karnig survived the 1915 Armenian Genocide and migrated to Sudan in 1923 where other Arabkir Armenians had already established themselves. A small number of Armenians from Arabkir and elsewhere had come to Sudan after the British conquest in 1899, mostly as an extension of trade networks from Egypt, with the hope of gaining wealth and supporting relatives in the homeland.

These early pioneers established a Sudan branch of the global Armenian charity AGBU (Armenian General Benevolent Union). Through the records of AGBU Sudan, preserved at the archives of AGBU in Cairo, we know that the early community came together to raise funds for compatriots in the Armenian Highlands who faced massacres, poverty, and eventually in 1915, Genocide at the hands of the Ottoman Empire.

Many of these Armenian men in Sudan, having lost their own families during the Genocide, responded to appeals from orphanages in Syria and Lebanon where many survivors had found refuge. Others, through much hardship, brought their surviving family members to Sudan. By the 1930s, a small group of Armenian traders had grown into a network of families spread across Sudan, from Atbara to Malakal and from Kassala to Al-Fashir, with the heart of the community in Khartoum.

Building a vibrant community in Sudan

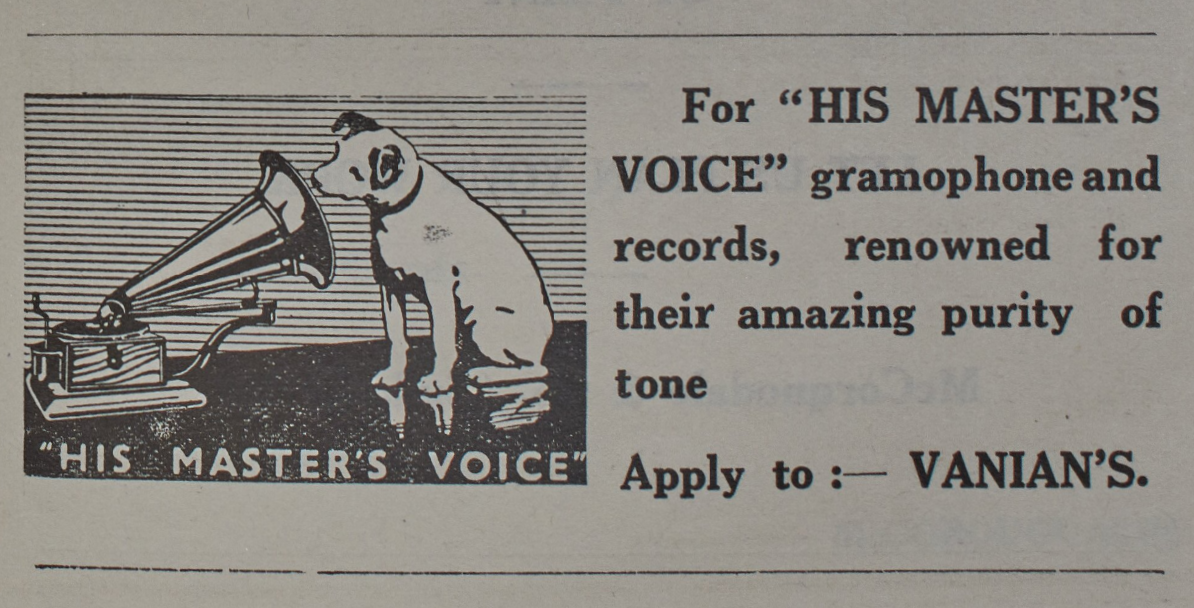

Their fluency in Arabic and English meant Armenians had an advantage in the job market and that they were respected and accepted by Sudanese society as well as by the governing British authorities. In this way, Karnig Yegavian found employment as an accountant at the National Bank of Egypt’s branch in Khartoum. Armenians, like the Greeks, Syrians, Jews and Italians, occupied a middle-ground in Sudan: adjacent to colonial power, but also working and living closely with Sudanese society. The dynamic of this relationship is further demonstrated by Andon Kazandjian, the Armenian photographer at Gordon Studios, the official photographers for the British authorities. The legacy of Armenian photographers like Kazandjian likely explains why so many photographs documenting the life of Armenians in Sudan have survived. While some like Andon provided services for the British, the majority of Armenians became traders, particularly as local dealers for Western companies or by establishing factories and industries. Karnig’s relative, Nerses Yegavian for example, worked for S & S Vanian, a department store in Khartoum known colloquially as the ‘Harrods of Africa’.

By the time Sudan gained independence in 1956, Armenians were a well-established and respected minority whose life, as a Christian “khawaja” community, revolved around the Armenian Church, Club, and School. After independence, members of the community became Sudanese citizens. At the time, Armenia was still part of the Soviet Union which meant, unlike other minorities, Armenians in Sudan had no original homelands to return to. Nevertheless, they were able to preserve their identity while living in Sudan through their faith, culture and family - whether through the church in Khartoum, an Armenian school in Gedaref, or in an Armenian home in Malakal.

The journey to decline

The Armenian community’s life was significantly disrupted in the late 1960s and 1970s when nationalisation policies were targeted against foreign businesses and individuals. Some Armenians left preemptively but others were forced to flee as result of the persecution. However, a number of Armenians preferred to remain and weather the political upheavals of the following decades while continuing to centre their community life around Armenian institutions in Khartoum.

As the political situation in the 1980s and onwards deteriorated, the community continued to shrink in size and the Armenian school eventually closed down due to a lack of students. The once-vibrant Armenian Club, often known as the place to be for Khartoum’s upper classes with its soirees and sporting events, was taken over by the authorities. In recent decades, the church remained the only community hub, serving approximately 50 Armenians in the 2000s, down from approximately 1,000 in the 1960s.

The Armenian Church stands to this day but like much of Khartoum, it now bears the scars of war and like millions of Sudanese, the remaining Sudanese-Armenians have also sought refuge outside the country. This departure marks an end to a community of over a hundred years and a legacy that saw Armenians co-exist with Sudanese to advance economy, pioneer industry and give birth to prominent achievers such as Zarouhi Sarkissian (Sudan’s first female doctor graduating in 1952 along with Khalda Zahir) or Jack Iskhanes (who advanced a unique Sudanese style of architecture). Whether Armenians will return, and what they will return to, remains to be seen. Yet, despite the political turmoil, many Sudanese-Armenians will proudly declare ‘Ana Sudani’, I am Sudanese, as they continue to be respected and welcomed in Sudanese society.

Cover picture: The Armenian School © Sudanahye picture archive

Sudanahye: the Sudanese-Armenian Heritage Project

Sudanese-Armenian cultural heritage, as part of Sudan’s broader, diverse cultural heritage, faces the threat of erasure. Previous limited attempts to document this community were small in scope, primarily academic and have made no material results accessible for Sudanese or Armenians.

It was within this context that the sudanahye (meaning Sudanese-Armenian in Armenian) project was conceived with the aim of creating an enduring legacy for this community via the development of an archive of Sudanese-Armenian history. What began as a personal effort to interview Sudanese-Armenians, has, with the support of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, grown into a multimedia project that seeks to document history, preserve heritage and re-imagine the community today by linking younger generations to their oral histories and archives.

The project’s director, Vahe Boghosian, is of Sudanese-Armenian origin and although he has never visited Sudan, he found the opportunity to work with like-minded Sudanese and Egyptians to set up a team when he moved to Cairo, where large Sudanese communities migrated following the war. His participation in numerous events related to culture, history, art and family archives in Cairo played a key role in integrating him into the Sudanese community. Throughout this period, he gained a deeper understanding of Sudanese culture, society and values.

As a result of these efforts, Sudanahye is piecing together stories of a community that were almost lost to time - stories that harness memories of a more pluralist past to help imagine a more co-existent future for Sudan.

On the banks of the Nile, a place of exile becomes a homeland

For so many Sudanese-Armenians, photos and stories about the long history of their life in Sudan were all they possessed to pass down to the next generation. They represented a real window onto the interaction of Armenian culture with the various aspects of Sudan’s diverse culture in all walks of life. The photos often show children at the Armenian school or portray a vibrant social scene at the Armenian Club, family picnics at Jebel Awliya or boat trips on the Nile - stories of belonging and co-existence.

Photos are usually taken to document happy times and as such, we find that most of these images and stories do not cover the history of exile, loss or deprivation suffered by Sudanese-Armenians. Unfortunately, when the war erupted in 2023, they were forced to relive a similar history which resulted in the loss of homes and lives including the death in their home in Khartoum of two cherished members of the community, the sisters Zvart and Arpi Yegavian. It is therefore necessary to document and preserve what remains and to establish a lasting heritage to ensure that their heritage, and that of their community is not lost.

Armenian migration from Arabkir to Sudan

The Yegavian sisters were descendants of Karnig Yegavian, an Armenian from Arabkir (a historic town in the Armenian Highlands which was later annexed by the Ottoman Empire and today forms part of eastern Turkey). Karnig survived the 1915 Armenian Genocide and migrated to Sudan in 1923 where other Arabkir Armenians had already established themselves. A small number of Armenians from Arabkir and elsewhere had come to Sudan after the British conquest in 1899, mostly as an extension of trade networks from Egypt, with the hope of gaining wealth and supporting relatives in the homeland.

These early pioneers established a Sudan branch of the global Armenian charity AGBU (Armenian General Benevolent Union). Through the records of AGBU Sudan, preserved at the archives of AGBU in Cairo, we know that the early community came together to raise funds for compatriots in the Armenian Highlands who faced massacres, poverty, and eventually in 1915, Genocide at the hands of the Ottoman Empire.

Many of these Armenian men in Sudan, having lost their own families during the Genocide, responded to appeals from orphanages in Syria and Lebanon where many survivors had found refuge. Others, through much hardship, brought their surviving family members to Sudan. By the 1930s, a small group of Armenian traders had grown into a network of families spread across Sudan, from Atbara to Malakal and from Kassala to Al-Fashir, with the heart of the community in Khartoum.

Building a vibrant community in Sudan

Their fluency in Arabic and English meant Armenians had an advantage in the job market and that they were respected and accepted by Sudanese society as well as by the governing British authorities. In this way, Karnig Yegavian found employment as an accountant at the National Bank of Egypt’s branch in Khartoum. Armenians, like the Greeks, Syrians, Jews and Italians, occupied a middle-ground in Sudan: adjacent to colonial power, but also working and living closely with Sudanese society. The dynamic of this relationship is further demonstrated by Andon Kazandjian, the Armenian photographer at Gordon Studios, the official photographers for the British authorities. The legacy of Armenian photographers like Kazandjian likely explains why so many photographs documenting the life of Armenians in Sudan have survived. While some like Andon provided services for the British, the majority of Armenians became traders, particularly as local dealers for Western companies or by establishing factories and industries. Karnig’s relative, Nerses Yegavian for example, worked for S & S Vanian, a department store in Khartoum known colloquially as the ‘Harrods of Africa’.

By the time Sudan gained independence in 1956, Armenians were a well-established and respected minority whose life, as a Christian “khawaja” community, revolved around the Armenian Church, Club, and School. After independence, members of the community became Sudanese citizens. At the time, Armenia was still part of the Soviet Union which meant, unlike other minorities, Armenians in Sudan had no original homelands to return to. Nevertheless, they were able to preserve their identity while living in Sudan through their faith, culture and family - whether through the church in Khartoum, an Armenian school in Gedaref, or in an Armenian home in Malakal.

The journey to decline

The Armenian community’s life was significantly disrupted in the late 1960s and 1970s when nationalisation policies were targeted against foreign businesses and individuals. Some Armenians left preemptively but others were forced to flee as result of the persecution. However, a number of Armenians preferred to remain and weather the political upheavals of the following decades while continuing to centre their community life around Armenian institutions in Khartoum.

As the political situation in the 1980s and onwards deteriorated, the community continued to shrink in size and the Armenian school eventually closed down due to a lack of students. The once-vibrant Armenian Club, often known as the place to be for Khartoum’s upper classes with its soirees and sporting events, was taken over by the authorities. In recent decades, the church remained the only community hub, serving approximately 50 Armenians in the 2000s, down from approximately 1,000 in the 1960s.

The Armenian Church stands to this day but like much of Khartoum, it now bears the scars of war and like millions of Sudanese, the remaining Sudanese-Armenians have also sought refuge outside the country. This departure marks an end to a community of over a hundred years and a legacy that saw Armenians co-exist with Sudanese to advance economy, pioneer industry and give birth to prominent achievers such as Zarouhi Sarkissian (Sudan’s first female doctor graduating in 1952 along with Khalda Zahir) or Jack Iskhanes (who advanced a unique Sudanese style of architecture). Whether Armenians will return, and what they will return to, remains to be seen. Yet, despite the political turmoil, many Sudanese-Armenians will proudly declare ‘Ana Sudani’, I am Sudanese, as they continue to be respected and welcomed in Sudanese society.

Cover picture: The Armenian School © Sudanahye picture archive

Sudanahye: the Sudanese-Armenian Heritage Project

Sudanese-Armenian cultural heritage, as part of Sudan’s broader, diverse cultural heritage, faces the threat of erasure. Previous limited attempts to document this community were small in scope, primarily academic and have made no material results accessible for Sudanese or Armenians.

It was within this context that the sudanahye (meaning Sudanese-Armenian in Armenian) project was conceived with the aim of creating an enduring legacy for this community via the development of an archive of Sudanese-Armenian history. What began as a personal effort to interview Sudanese-Armenians, has, with the support of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, grown into a multimedia project that seeks to document history, preserve heritage and re-imagine the community today by linking younger generations to their oral histories and archives.

The project’s director, Vahe Boghosian, is of Sudanese-Armenian origin and although he has never visited Sudan, he found the opportunity to work with like-minded Sudanese and Egyptians to set up a team when he moved to Cairo, where large Sudanese communities migrated following the war. His participation in numerous events related to culture, history, art and family archives in Cairo played a key role in integrating him into the Sudanese community. Throughout this period, he gained a deeper understanding of Sudanese culture, society and values.

As a result of these efforts, Sudanahye is piecing together stories of a community that were almost lost to time - stories that harness memories of a more pluralist past to help imagine a more co-existent future for Sudan.

On the banks of the Nile, a place of exile becomes a homeland

For so many Sudanese-Armenians, photos and stories about the long history of their life in Sudan were all they possessed to pass down to the next generation. They represented a real window onto the interaction of Armenian culture with the various aspects of Sudan’s diverse culture in all walks of life. The photos often show children at the Armenian school or portray a vibrant social scene at the Armenian Club, family picnics at Jebel Awliya or boat trips on the Nile - stories of belonging and co-existence.

Photos are usually taken to document happy times and as such, we find that most of these images and stories do not cover the history of exile, loss or deprivation suffered by Sudanese-Armenians. Unfortunately, when the war erupted in 2023, they were forced to relive a similar history which resulted in the loss of homes and lives including the death in their home in Khartoum of two cherished members of the community, the sisters Zvart and Arpi Yegavian. It is therefore necessary to document and preserve what remains and to establish a lasting heritage to ensure that their heritage, and that of their community is not lost.

Armenian migration from Arabkir to Sudan

The Yegavian sisters were descendants of Karnig Yegavian, an Armenian from Arabkir (a historic town in the Armenian Highlands which was later annexed by the Ottoman Empire and today forms part of eastern Turkey). Karnig survived the 1915 Armenian Genocide and migrated to Sudan in 1923 where other Arabkir Armenians had already established themselves. A small number of Armenians from Arabkir and elsewhere had come to Sudan after the British conquest in 1899, mostly as an extension of trade networks from Egypt, with the hope of gaining wealth and supporting relatives in the homeland.

These early pioneers established a Sudan branch of the global Armenian charity AGBU (Armenian General Benevolent Union). Through the records of AGBU Sudan, preserved at the archives of AGBU in Cairo, we know that the early community came together to raise funds for compatriots in the Armenian Highlands who faced massacres, poverty, and eventually in 1915, Genocide at the hands of the Ottoman Empire.

Many of these Armenian men in Sudan, having lost their own families during the Genocide, responded to appeals from orphanages in Syria and Lebanon where many survivors had found refuge. Others, through much hardship, brought their surviving family members to Sudan. By the 1930s, a small group of Armenian traders had grown into a network of families spread across Sudan, from Atbara to Malakal and from Kassala to Al-Fashir, with the heart of the community in Khartoum.

Building a vibrant community in Sudan

Their fluency in Arabic and English meant Armenians had an advantage in the job market and that they were respected and accepted by Sudanese society as well as by the governing British authorities. In this way, Karnig Yegavian found employment as an accountant at the National Bank of Egypt’s branch in Khartoum. Armenians, like the Greeks, Syrians, Jews and Italians, occupied a middle-ground in Sudan: adjacent to colonial power, but also working and living closely with Sudanese society. The dynamic of this relationship is further demonstrated by Andon Kazandjian, the Armenian photographer at Gordon Studios, the official photographers for the British authorities. The legacy of Armenian photographers like Kazandjian likely explains why so many photographs documenting the life of Armenians in Sudan have survived. While some like Andon provided services for the British, the majority of Armenians became traders, particularly as local dealers for Western companies or by establishing factories and industries. Karnig’s relative, Nerses Yegavian for example, worked for S & S Vanian, a department store in Khartoum known colloquially as the ‘Harrods of Africa’.

By the time Sudan gained independence in 1956, Armenians were a well-established and respected minority whose life, as a Christian “khawaja” community, revolved around the Armenian Church, Club, and School. After independence, members of the community became Sudanese citizens. At the time, Armenia was still part of the Soviet Union which meant, unlike other minorities, Armenians in Sudan had no original homelands to return to. Nevertheless, they were able to preserve their identity while living in Sudan through their faith, culture and family - whether through the church in Khartoum, an Armenian school in Gedaref, or in an Armenian home in Malakal.

The journey to decline

The Armenian community’s life was significantly disrupted in the late 1960s and 1970s when nationalisation policies were targeted against foreign businesses and individuals. Some Armenians left preemptively but others were forced to flee as result of the persecution. However, a number of Armenians preferred to remain and weather the political upheavals of the following decades while continuing to centre their community life around Armenian institutions in Khartoum.

As the political situation in the 1980s and onwards deteriorated, the community continued to shrink in size and the Armenian school eventually closed down due to a lack of students. The once-vibrant Armenian Club, often known as the place to be for Khartoum’s upper classes with its soirees and sporting events, was taken over by the authorities. In recent decades, the church remained the only community hub, serving approximately 50 Armenians in the 2000s, down from approximately 1,000 in the 1960s.

The Armenian Church stands to this day but like much of Khartoum, it now bears the scars of war and like millions of Sudanese, the remaining Sudanese-Armenians have also sought refuge outside the country. This departure marks an end to a community of over a hundred years and a legacy that saw Armenians co-exist with Sudanese to advance economy, pioneer industry and give birth to prominent achievers such as Zarouhi Sarkissian (Sudan’s first female doctor graduating in 1952 along with Khalda Zahir) or Jack Iskhanes (who advanced a unique Sudanese style of architecture). Whether Armenians will return, and what they will return to, remains to be seen. Yet, despite the political turmoil, many Sudanese-Armenians will proudly declare ‘Ana Sudani’, I am Sudanese, as they continue to be respected and welcomed in Sudanese society.

Cover picture: The Armenian School © Sudanahye picture archive

Tayfour

Tayfour

A wooden bowl with a cover and, a cylindrical shape, it is made of wood, and used for keeping dry fragrance, it is part of tools that are used in wedding ceremonies all around Sudan

Used since ancient times up to today

Darfur museum collection

A wooden bowl with a cover and, a cylindrical shape, it is made of wood, and used for keeping dry fragrance, it is part of tools that are used in wedding ceremonies all around Sudan

Used since ancient times up to today

Darfur museum collection

A wooden bowl with a cover and, a cylindrical shape, it is made of wood, and used for keeping dry fragrance, it is part of tools that are used in wedding ceremonies all around Sudan

Used since ancient times up to today

Darfur museum collection

Connecting Communities

Connecting Communities

Connecting Communities: How Surveys Promote Understanding and Coexisting

Surveys are more than just a way to gather data; they are powerful tools that can help build understanding and peace, especially among communities marked by cultural diversity or where conflict has emerged. By asking the right questions, surveys help uncover common ground, highlight shared experiences, and bring different groups together. In societies where divisions run deep, surveys can provide a neutral space for conversation and reconciliation, making them vital for promoting peaceful coexistence.

At their core, surveys are designed to collect perspectives and experiences from people, helping us understand their needs, values, and concerns. The strength of surveys lies in their ability to reach diverse communities, ensuring that every voice is heard. In areas where tensions exist, whether due to ethnicity, religion, or politics, surveys can reveal that people, regardless of background, often share similar hopes, challenges, and desires. These shared experiences can be a starting point for building empathy and breaking down barriers.

For example, surveys conducted in post-conflict zones can uncover underlying issues like access to education, healthcare, or economic opportunity. These common concerns highlight the ways different groups face similar challenges, encouraging them to focus on what unites them rather than what divides them. By bringing attention to shared issues, surveys help foster dialogue between communities, creating a foundation for collaboration and peace.

One particularly powerful example of this comes from Sudan, where surveys have been used as tools for inclusion. The Darfur Material Culture Survey was a great illustration of how surveys can connect people across different cultural and ethnic backgrounds. It was conducted by the Institute of African and Asian Studies in collaboration with Nyala University and teams of researchers from all across Darfur. It was conducted in partnership with the Western Sudan Community Museums project and the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM). The researchers documented everyday objects like agricultural tools, cooking implements, and traditional footwear—items that, while designed in different ways depending on the region, served similar functions in people’s daily lives.

One notable object was the markoob a type of traditional leather shoe worn throughout Sudan. Though the leather and designs vary from one area to another, the markoob serves the same purpose: providing comfort and protection. This simple object speaks to the shared cultural practices that cut across ethnic lines. Similarly, the pottery used for cooking and storing food in Sudan’s diverse communities has common features, reflecting similar ways of adapting to each region's environment.

By highlighting these shared practices, this material culture survey did more than document cultural artefacts by helping to create a sense of unity. People from different backgrounds saw their own traditions reflected in the items of others, sparking a sense of connection. The exhibition showcasing the survey’s outcome which was organised by the Western Sudan Community Museums at the Darfur Museum in Nyala allowed visitors to engage with these objects, and by doing so, they were reminded of the common values and experiences they share. This kind of cultural exchange helps bridge divides, turning differences into opportunities for mutual understanding.

Surveys also play an important role in identifying sources of differences, which is crucial for peacebuilding efforts. These insights allow policymakers and community leaders to address the root causes of conflict and work towards solutions that benefit everyone. In this way, surveys act as a kind of diagnostic tool for societies in need of common ground to prompt unity.

Another significant benefit of surveys is that they give a voice to those who are often marginalized or excluded from the conversation. In many conflict-prone regions, some groups – whether based on ethnicity, gender, or age – feel left out of key decision-making processes. Surveys provide an opportunity for these groups to share their experiences and perspectives. When people who feel unheard are included in the dialogue, it not only empowers them but also ensures that peacebuilding efforts are more inclusive and representative of the entire community.

Trust and transparency are also key elements of any successful peace process, and surveys help build both. In post-conflict societies, trust between different groups can be fragile. By assessing how people view institutions, such as the government or local leaders, surveys provide valuable insights into the state of social trust. Understanding what factors strengthen or weaken trust in a community allows peacebuilders to design interventions that address these issues, whether through community engagement, or rebuilding social institutions.

In Sudan, surveys like the one conducted by Nyala University with research teams from all over Darfur help foster trust by focusing on the things that unite rather than divide. By highlighting shared cultural practices, these surveys create a platform for dialogue that encourages people to see one another as neighbours. This approach helps shift the focus from differences to common goals, laying the groundwork for long-term peace and stability.

Surveys also offer a way to track progress in peacebuilding efforts. In societies recovering from conflict, it is important to measure whether inclusion efforts are making a real impact. By gathering data on people’s attitudes towards their communities, traditions, and culture, surveys provide critical feedback for governments, NGOs, development initiatives, heritage preservation initiatives and different organizations. This ongoing assessment ensures that inclusion and peacebuilding strategies are evolving to meet the needs of the population and remain effective over time.

All in all, surveys are more than just tools for collecting data, they are instruments for promoting peaceful coexistence. By highlighting shared practices, ways of life, uncovering similarities, and giving marginalized voices a platform, surveys help bridge divides and foster understanding. The example of the Darfur Material Culture Survey in Sudan shows how surveys can bring communities together, using common cultural practices as a foundation for unity. Ultimately, surveys provide a way for societies to reflect on what they have in common, helping to build understanding and cooperation needed to move toward lasting peace and harmony.

Cover picture: Markob seller, The cities of Nyala and El Fashir are famous for making traditional shoes called markob, which are men's shoes made of animal skins.© Issam Ahmed Abdelhafiez, South Darfur

Connecting Communities: How Surveys Promote Understanding and Coexisting

Surveys are more than just a way to gather data; they are powerful tools that can help build understanding and peace, especially among communities marked by cultural diversity or where conflict has emerged. By asking the right questions, surveys help uncover common ground, highlight shared experiences, and bring different groups together. In societies where divisions run deep, surveys can provide a neutral space for conversation and reconciliation, making them vital for promoting peaceful coexistence.

At their core, surveys are designed to collect perspectives and experiences from people, helping us understand their needs, values, and concerns. The strength of surveys lies in their ability to reach diverse communities, ensuring that every voice is heard. In areas where tensions exist, whether due to ethnicity, religion, or politics, surveys can reveal that people, regardless of background, often share similar hopes, challenges, and desires. These shared experiences can be a starting point for building empathy and breaking down barriers.

For example, surveys conducted in post-conflict zones can uncover underlying issues like access to education, healthcare, or economic opportunity. These common concerns highlight the ways different groups face similar challenges, encouraging them to focus on what unites them rather than what divides them. By bringing attention to shared issues, surveys help foster dialogue between communities, creating a foundation for collaboration and peace.

One particularly powerful example of this comes from Sudan, where surveys have been used as tools for inclusion. The Darfur Material Culture Survey was a great illustration of how surveys can connect people across different cultural and ethnic backgrounds. It was conducted by the Institute of African and Asian Studies in collaboration with Nyala University and teams of researchers from all across Darfur. It was conducted in partnership with the Western Sudan Community Museums project and the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM). The researchers documented everyday objects like agricultural tools, cooking implements, and traditional footwear—items that, while designed in different ways depending on the region, served similar functions in people’s daily lives.

One notable object was the markoob a type of traditional leather shoe worn throughout Sudan. Though the leather and designs vary from one area to another, the markoob serves the same purpose: providing comfort and protection. This simple object speaks to the shared cultural practices that cut across ethnic lines. Similarly, the pottery used for cooking and storing food in Sudan’s diverse communities has common features, reflecting similar ways of adapting to each region's environment.

By highlighting these shared practices, this material culture survey did more than document cultural artefacts by helping to create a sense of unity. People from different backgrounds saw their own traditions reflected in the items of others, sparking a sense of connection. The exhibition showcasing the survey’s outcome which was organised by the Western Sudan Community Museums at the Darfur Museum in Nyala allowed visitors to engage with these objects, and by doing so, they were reminded of the common values and experiences they share. This kind of cultural exchange helps bridge divides, turning differences into opportunities for mutual understanding.

Surveys also play an important role in identifying sources of differences, which is crucial for peacebuilding efforts. These insights allow policymakers and community leaders to address the root causes of conflict and work towards solutions that benefit everyone. In this way, surveys act as a kind of diagnostic tool for societies in need of common ground to prompt unity.

Another significant benefit of surveys is that they give a voice to those who are often marginalized or excluded from the conversation. In many conflict-prone regions, some groups – whether based on ethnicity, gender, or age – feel left out of key decision-making processes. Surveys provide an opportunity for these groups to share their experiences and perspectives. When people who feel unheard are included in the dialogue, it not only empowers them but also ensures that peacebuilding efforts are more inclusive and representative of the entire community.

Trust and transparency are also key elements of any successful peace process, and surveys help build both. In post-conflict societies, trust between different groups can be fragile. By assessing how people view institutions, such as the government or local leaders, surveys provide valuable insights into the state of social trust. Understanding what factors strengthen or weaken trust in a community allows peacebuilders to design interventions that address these issues, whether through community engagement, or rebuilding social institutions.

In Sudan, surveys like the one conducted by Nyala University with research teams from all over Darfur help foster trust by focusing on the things that unite rather than divide. By highlighting shared cultural practices, these surveys create a platform for dialogue that encourages people to see one another as neighbours. This approach helps shift the focus from differences to common goals, laying the groundwork for long-term peace and stability.

Surveys also offer a way to track progress in peacebuilding efforts. In societies recovering from conflict, it is important to measure whether inclusion efforts are making a real impact. By gathering data on people’s attitudes towards their communities, traditions, and culture, surveys provide critical feedback for governments, NGOs, development initiatives, heritage preservation initiatives and different organizations. This ongoing assessment ensures that inclusion and peacebuilding strategies are evolving to meet the needs of the population and remain effective over time.

All in all, surveys are more than just tools for collecting data, they are instruments for promoting peaceful coexistence. By highlighting shared practices, ways of life, uncovering similarities, and giving marginalized voices a platform, surveys help bridge divides and foster understanding. The example of the Darfur Material Culture Survey in Sudan shows how surveys can bring communities together, using common cultural practices as a foundation for unity. Ultimately, surveys provide a way for societies to reflect on what they have in common, helping to build understanding and cooperation needed to move toward lasting peace and harmony.

Cover picture: Markob seller, The cities of Nyala and El Fashir are famous for making traditional shoes called markob, which are men's shoes made of animal skins.© Issam Ahmed Abdelhafiez, South Darfur

Connecting Communities: How Surveys Promote Understanding and Coexisting

Surveys are more than just a way to gather data; they are powerful tools that can help build understanding and peace, especially among communities marked by cultural diversity or where conflict has emerged. By asking the right questions, surveys help uncover common ground, highlight shared experiences, and bring different groups together. In societies where divisions run deep, surveys can provide a neutral space for conversation and reconciliation, making them vital for promoting peaceful coexistence.

At their core, surveys are designed to collect perspectives and experiences from people, helping us understand their needs, values, and concerns. The strength of surveys lies in their ability to reach diverse communities, ensuring that every voice is heard. In areas where tensions exist, whether due to ethnicity, religion, or politics, surveys can reveal that people, regardless of background, often share similar hopes, challenges, and desires. These shared experiences can be a starting point for building empathy and breaking down barriers.

For example, surveys conducted in post-conflict zones can uncover underlying issues like access to education, healthcare, or economic opportunity. These common concerns highlight the ways different groups face similar challenges, encouraging them to focus on what unites them rather than what divides them. By bringing attention to shared issues, surveys help foster dialogue between communities, creating a foundation for collaboration and peace.

One particularly powerful example of this comes from Sudan, where surveys have been used as tools for inclusion. The Darfur Material Culture Survey was a great illustration of how surveys can connect people across different cultural and ethnic backgrounds. It was conducted by the Institute of African and Asian Studies in collaboration with Nyala University and teams of researchers from all across Darfur. It was conducted in partnership with the Western Sudan Community Museums project and the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM). The researchers documented everyday objects like agricultural tools, cooking implements, and traditional footwear—items that, while designed in different ways depending on the region, served similar functions in people’s daily lives.

One notable object was the markoob a type of traditional leather shoe worn throughout Sudan. Though the leather and designs vary from one area to another, the markoob serves the same purpose: providing comfort and protection. This simple object speaks to the shared cultural practices that cut across ethnic lines. Similarly, the pottery used for cooking and storing food in Sudan’s diverse communities has common features, reflecting similar ways of adapting to each region's environment.

By highlighting these shared practices, this material culture survey did more than document cultural artefacts by helping to create a sense of unity. People from different backgrounds saw their own traditions reflected in the items of others, sparking a sense of connection. The exhibition showcasing the survey’s outcome which was organised by the Western Sudan Community Museums at the Darfur Museum in Nyala allowed visitors to engage with these objects, and by doing so, they were reminded of the common values and experiences they share. This kind of cultural exchange helps bridge divides, turning differences into opportunities for mutual understanding.

Surveys also play an important role in identifying sources of differences, which is crucial for peacebuilding efforts. These insights allow policymakers and community leaders to address the root causes of conflict and work towards solutions that benefit everyone. In this way, surveys act as a kind of diagnostic tool for societies in need of common ground to prompt unity.

Another significant benefit of surveys is that they give a voice to those who are often marginalized or excluded from the conversation. In many conflict-prone regions, some groups – whether based on ethnicity, gender, or age – feel left out of key decision-making processes. Surveys provide an opportunity for these groups to share their experiences and perspectives. When people who feel unheard are included in the dialogue, it not only empowers them but also ensures that peacebuilding efforts are more inclusive and representative of the entire community.

Trust and transparency are also key elements of any successful peace process, and surveys help build both. In post-conflict societies, trust between different groups can be fragile. By assessing how people view institutions, such as the government or local leaders, surveys provide valuable insights into the state of social trust. Understanding what factors strengthen or weaken trust in a community allows peacebuilders to design interventions that address these issues, whether through community engagement, or rebuilding social institutions.

In Sudan, surveys like the one conducted by Nyala University with research teams from all over Darfur help foster trust by focusing on the things that unite rather than divide. By highlighting shared cultural practices, these surveys create a platform for dialogue that encourages people to see one another as neighbours. This approach helps shift the focus from differences to common goals, laying the groundwork for long-term peace and stability.

Surveys also offer a way to track progress in peacebuilding efforts. In societies recovering from conflict, it is important to measure whether inclusion efforts are making a real impact. By gathering data on people’s attitudes towards their communities, traditions, and culture, surveys provide critical feedback for governments, NGOs, development initiatives, heritage preservation initiatives and different organizations. This ongoing assessment ensures that inclusion and peacebuilding strategies are evolving to meet the needs of the population and remain effective over time.

All in all, surveys are more than just tools for collecting data, they are instruments for promoting peaceful coexistence. By highlighting shared practices, ways of life, uncovering similarities, and giving marginalized voices a platform, surveys help bridge divides and foster understanding. The example of the Darfur Material Culture Survey in Sudan shows how surveys can bring communities together, using common cultural practices as a foundation for unity. Ultimately, surveys provide a way for societies to reflect on what they have in common, helping to build understanding and cooperation needed to move toward lasting peace and harmony.

Cover picture: Markob seller, The cities of Nyala and El Fashir are famous for making traditional shoes called markob, which are men's shoes made of animal skins.© Issam Ahmed Abdelhafiez, South Darfur

Games and toys

Games and toys

A ‘game’ refers to anything used for play, such as a toy or doll, or an activity meant for entertainment or as a pastime. Its plural form is ‘games’. When we say, ‘a child plays’, it means they are engaging in activities for fun and distraction.

The term refers to the game itself, and the objects used for playing.

Games and Their Terminologies in Sudan

Traditional Sudanese games come in many forms, ranging from chasing and speed-based games such as tag sak-sak, hide and seek korkat or dasdas, daisy in the dell alfat alfat. These games often involve a ‘finish line’ or a specific location referred to as al-miys, which serves as the safe zone players must reach to win. The term al-tish is used for the player who lags behind or performs the weakest, often becoming ‘it’ in the next round. Other games involving precision and strategy include marbles billi and kambalat similar to piggy in the middle. Some games have different names depending on the region they come from but they often share similar rules. For instance, sakkaj bakkaj, a game played across Sudan is also known as tik trak, kobri, adi, sola, and al-daghal. Needless to say whatever the name, children all over Sudan always have a great time playing these games.

● Shilail: A traditional game where an object like, a bone or stone is hidden to be found.

● Al-Tarha: A game that involves grabbing and running away with a length of cloth or object.

● Joz, Loz, Koz, Moz: A paper game played by 4 or more.

Cover picture © Amani Basheer, Obaid, Recording Intangible Cultural Heritage workshop.

A ‘game’ refers to anything used for play, such as a toy or doll, or an activity meant for entertainment or as a pastime. Its plural form is ‘games’. When we say, ‘a child plays’, it means they are engaging in activities for fun and distraction.

The term refers to the game itself, and the objects used for playing.

Games and Their Terminologies in Sudan

Traditional Sudanese games come in many forms, ranging from chasing and speed-based games such as tag sak-sak, hide and seek korkat or dasdas, daisy in the dell alfat alfat. These games often involve a ‘finish line’ or a specific location referred to as al-miys, which serves as the safe zone players must reach to win. The term al-tish is used for the player who lags behind or performs the weakest, often becoming ‘it’ in the next round. Other games involving precision and strategy include marbles billi and kambalat similar to piggy in the middle. Some games have different names depending on the region they come from but they often share similar rules. For instance, sakkaj bakkaj, a game played across Sudan is also known as tik trak, kobri, adi, sola, and al-daghal. Needless to say whatever the name, children all over Sudan always have a great time playing these games.

● Shilail: A traditional game where an object like, a bone or stone is hidden to be found.

● Al-Tarha: A game that involves grabbing and running away with a length of cloth or object.

● Joz, Loz, Koz, Moz: A paper game played by 4 or more.

Cover picture © Amani Basheer, Obaid, Recording Intangible Cultural Heritage workshop.

A ‘game’ refers to anything used for play, such as a toy or doll, or an activity meant for entertainment or as a pastime. Its plural form is ‘games’. When we say, ‘a child plays’, it means they are engaging in activities for fun and distraction.

The term refers to the game itself, and the objects used for playing.

Games and Their Terminologies in Sudan

Traditional Sudanese games come in many forms, ranging from chasing and speed-based games such as tag sak-sak, hide and seek korkat or dasdas, daisy in the dell alfat alfat. These games often involve a ‘finish line’ or a specific location referred to as al-miys, which serves as the safe zone players must reach to win. The term al-tish is used for the player who lags behind or performs the weakest, often becoming ‘it’ in the next round. Other games involving precision and strategy include marbles billi and kambalat similar to piggy in the middle. Some games have different names depending on the region they come from but they often share similar rules. For instance, sakkaj bakkaj, a game played across Sudan is also known as tik trak, kobri, adi, sola, and al-daghal. Needless to say whatever the name, children all over Sudan always have a great time playing these games.

● Shilail: A traditional game where an object like, a bone or stone is hidden to be found.

● Al-Tarha: A game that involves grabbing and running away with a length of cloth or object.

● Joz, Loz, Koz, Moz: A paper game played by 4 or more.

Cover picture © Amani Basheer, Obaid, Recording Intangible Cultural Heritage workshop.

Lawh and Dawaya

Lawh and Dawaya

Lawh is a small Wooden board used for teaching the Quran, Some Quran verses were written in one sides, in the name of Allah the Merciful (بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم), written on it with special ink called Ammar it consists of glue and black soot.

A pot of ink (Dawaya) is made of gourd with a hole in the top and stopper woven around with rope, and three pens of wicker stems. Found in Nyala dates back to Islamic period.

Darfur museum collection

Lawh is a small Wooden board used for teaching the Quran, Some Quran verses were written in one sides, in the name of Allah the Merciful (بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم), written on it with special ink called Ammar it consists of glue and black soot.

A pot of ink (Dawaya) is made of gourd with a hole in the top and stopper woven around with rope, and three pens of wicker stems. Found in Nyala dates back to Islamic period.

Darfur museum collection

Lawh is a small Wooden board used for teaching the Quran, Some Quran verses were written in one sides, in the name of Allah the Merciful (بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم), written on it with special ink called Ammar it consists of glue and black soot.

A pot of ink (Dawaya) is made of gourd with a hole in the top and stopper woven around with rope, and three pens of wicker stems. Found in Nyala dates back to Islamic period.

Darfur museum collection

Fashionable connections

Fashionable connections

Many traditional Sudanese garments have been tailored and designed for practical reasons to help cope with the hot climate, work needs and even as at times of war. Many of the clothes we associate with the Sudanese national dress are also worn in other areas in Sub-Saharan Africa, especially the women’s sari-like garment, tob, and the men’s gown, jallabiyya.

The jallabiyya, a wide, A-shaped gown is popular all around Africa including countries with Arab influence. Worn extensively around Sudan, there are minor differences in the style of jallabiyya according to the geographic location. One distinctive type of jallabiyya is the ansariyya which was popularized during the period of the Mahdiyya as a garment that can be donned at haste when there was a call for battle. The front and back of this jallabiyya are identical, with sides having a pocket sewn on. The garment’s A- shape was ideal for horse-riding and participating in combat.

Varieties of the Sudanese women’s tob can also be found throughout Sudan and in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa; everywhere from Mauritania, Nigeria and Chad, to southern Libya and have names such as laffaya, melhfa and dampe. There are a variety of ways in which the tob is worn in these different countries; from the length of the fabric to how it is wrapped around the body. This is the same in Sudan where ways of wearing the tob vary with styles being influenced for example by the women’s work whether it is farming, herding or just everyday housework.

Today the tob has become the object of fashion statements with artists in all these countries competing with new design ideas and European factories producing these designs, and new fabrics, every year. However, these slippery, silky and heavily sequined designs have rendered this type of tob completely impractical for everyday use and they are only worn on special occasions by married women. Cultural connections between the residents of the sub-saharan sahel region was generally thought to be the main reason for the popularity of the tob here however, academics point to the practical adaptation of the garment to the heat, strong sunlight and dry air that characterises the region’s climate. Wearing long, flowing, light-coloured gowns that cover the head, and which produce air pockets around the body, is an ideal design to keep both men and women cool in the heat.

Another versatile item of clothing is the leather shoe, markoob, worn predominantly by men in most parts of Sudan. The type of markoob depends on what leather is available and can include the skins of anything from rock pythons and leopards to humble cow hide. This traditional type of footwear is also seeing a resurgence and makeover with young Sudanese entrepreneurs creating colourful designs of the markoob for both men and women.

Cover picture: Three sets of men's jallabiyya, 1. Traditional men's wear with front and back pockets (Ansariyya). 2. Traditional men's wear consists of four pieces (Jiba, Aragi, Sirwal, Taqiya). 3.Traditional men's wear of the Baggara tribe (Bagariyya) © Darfur Women’s Museum

Many traditional Sudanese garments have been tailored and designed for practical reasons to help cope with the hot climate, work needs and even as at times of war. Many of the clothes we associate with the Sudanese national dress are also worn in other areas in Sub-Saharan Africa, especially the women’s sari-like garment, tob, and the men’s gown, jallabiyya.

The jallabiyya, a wide, A-shaped gown is popular all around Africa including countries with Arab influence. Worn extensively around Sudan, there are minor differences in the style of jallabiyya according to the geographic location. One distinctive type of jallabiyya is the ansariyya which was popularized during the period of the Mahdiyya as a garment that can be donned at haste when there was a call for battle. The front and back of this jallabiyya are identical, with sides having a pocket sewn on. The garment’s A- shape was ideal for horse-riding and participating in combat.

Varieties of the Sudanese women’s tob can also be found throughout Sudan and in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa; everywhere from Mauritania, Nigeria and Chad, to southern Libya and have names such as laffaya, melhfa and dampe. There are a variety of ways in which the tob is worn in these different countries; from the length of the fabric to how it is wrapped around the body. This is the same in Sudan where ways of wearing the tob vary with styles being influenced for example by the women’s work whether it is farming, herding or just everyday housework.

Today the tob has become the object of fashion statements with artists in all these countries competing with new design ideas and European factories producing these designs, and new fabrics, every year. However, these slippery, silky and heavily sequined designs have rendered this type of tob completely impractical for everyday use and they are only worn on special occasions by married women. Cultural connections between the residents of the sub-saharan sahel region was generally thought to be the main reason for the popularity of the tob here however, academics point to the practical adaptation of the garment to the heat, strong sunlight and dry air that characterises the region’s climate. Wearing long, flowing, light-coloured gowns that cover the head, and which produce air pockets around the body, is an ideal design to keep both men and women cool in the heat.

Another versatile item of clothing is the leather shoe, markoob, worn predominantly by men in most parts of Sudan. The type of markoob depends on what leather is available and can include the skins of anything from rock pythons and leopards to humble cow hide. This traditional type of footwear is also seeing a resurgence and makeover with young Sudanese entrepreneurs creating colourful designs of the markoob for both men and women.

Cover picture: Three sets of men's jallabiyya, 1. Traditional men's wear with front and back pockets (Ansariyya). 2. Traditional men's wear consists of four pieces (Jiba, Aragi, Sirwal, Taqiya). 3.Traditional men's wear of the Baggara tribe (Bagariyya) © Darfur Women’s Museum

Many traditional Sudanese garments have been tailored and designed for practical reasons to help cope with the hot climate, work needs and even as at times of war. Many of the clothes we associate with the Sudanese national dress are also worn in other areas in Sub-Saharan Africa, especially the women’s sari-like garment, tob, and the men’s gown, jallabiyya.

The jallabiyya, a wide, A-shaped gown is popular all around Africa including countries with Arab influence. Worn extensively around Sudan, there are minor differences in the style of jallabiyya according to the geographic location. One distinctive type of jallabiyya is the ansariyya which was popularized during the period of the Mahdiyya as a garment that can be donned at haste when there was a call for battle. The front and back of this jallabiyya are identical, with sides having a pocket sewn on. The garment’s A- shape was ideal for horse-riding and participating in combat.

Varieties of the Sudanese women’s tob can also be found throughout Sudan and in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa; everywhere from Mauritania, Nigeria and Chad, to southern Libya and have names such as laffaya, melhfa and dampe. There are a variety of ways in which the tob is worn in these different countries; from the length of the fabric to how it is wrapped around the body. This is the same in Sudan where ways of wearing the tob vary with styles being influenced for example by the women’s work whether it is farming, herding or just everyday housework.

Today the tob has become the object of fashion statements with artists in all these countries competing with new design ideas and European factories producing these designs, and new fabrics, every year. However, these slippery, silky and heavily sequined designs have rendered this type of tob completely impractical for everyday use and they are only worn on special occasions by married women. Cultural connections between the residents of the sub-saharan sahel region was generally thought to be the main reason for the popularity of the tob here however, academics point to the practical adaptation of the garment to the heat, strong sunlight and dry air that characterises the region’s climate. Wearing long, flowing, light-coloured gowns that cover the head, and which produce air pockets around the body, is an ideal design to keep both men and women cool in the heat.

Another versatile item of clothing is the leather shoe, markoob, worn predominantly by men in most parts of Sudan. The type of markoob depends on what leather is available and can include the skins of anything from rock pythons and leopards to humble cow hide. This traditional type of footwear is also seeing a resurgence and makeover with young Sudanese entrepreneurs creating colourful designs of the markoob for both men and women.

Cover picture: Three sets of men's jallabiyya, 1. Traditional men's wear with front and back pockets (Ansariyya). 2. Traditional men's wear consists of four pieces (Jiba, Aragi, Sirwal, Taqiya). 3.Traditional men's wear of the Baggara tribe (Bagariyya) © Darfur Women’s Museum

The blessed land

The blessed land

I remember when I was at university my friend suddenly cried, “oh, I’m really craving some silt from the river”. At the time, this sounded very strange to me as I was still discovering Sudan and the Sudanese because I was what’s known as ‘shahada Arabia’ - a Sudanese expatriate living in the Arabian Gulf. My knowledge of Sudan was still limited to my village, Ishkit, south of Village 13 in Kassala State and I wasn’t very familiar with Khartoum.

However, after what my friend said, I inadvertently began observing the people around me and tried to understand them and how they loved their country so much they even had a craving for its mud. I admired their deep connection to Sudan, and this feeling became the driving force behind the foundation of ‘Shorrti : Spirit of the place,’ a project which aims to introduce Sudanese people to Sudan and its cultural, environmental and ethnic diversity through events and cultural trips where we explore the different elements of this homeland, including music, heritage, and history.

Shorrti launched in 2016 and since then, we have organized over 54 events in Khartoum and other cities, and have visited over 30 villages and cities in 11 states. In every village or city we visited, more people joined our Shorrti community until eventually, we created our own small village that represented the entire Sudan and dissolved the boundaries of our home towns and cities. We became more connected to the different forms of heritage and to Sudan as a whole and every new person I meet, my understanding of the connection to this land deepens.

I remember that at one particular Shorrti event, I spoke with a man from the Jabal Marra region who told me about an old custom from the time of his ancestors, where they would plant a tree for every newborn and name it after the child. It was as if they were linking their children to the land, creating in them a sense of belonging and connection to their roots. I felt then that the Sudanese people not only love their land, but also carry a special connection to their predecessors buried there. This is reflected in our social and family structures, where we place great importance on the blessing and prayers of our elders. Through our journeys criss-crossing Sudan, I learned that most communities maintain a close connection to their forebears and always have a strong need to receive their blessings.

On our first trip to the Nuri area, specifically to the island of Tarag, there is a mosque and a number of shrines most notably built for the sons of Jaber who were among the first to be taught by Sheikh Ghulam al-Din bin Ayid, founder of the first khalwa in Dongola. However, what caught my attention was the shrine of a sheikh that did not have a dome and which was surrounded by a metal fence with palm fronds attached randomly. When I asked about the reason the fronds were tied there, our guide told me that those who wanted to marry would come here and tie their fronds to the fence and pray to God to grant their wish. This reminded me of the Lovers' Bridge in France where lovers attach padlocks as a symbol of their bond.

As we headed north, accompanied by the melodious sound of the Nile cascading over the sixth to the third cataract, we arrived in Tumbus and the site of 'Okji Nunondi,' a statue lying in the sand. We were told that the statue’s name translates into 'nobleman' or 'knight,' although a more literal translation would be ‘virile man’. This unidentified statue is not only a tourist attraction but has also been a symbol of hope and fertility for thousands of years and has been visited by countless men and women from the region hoping to enhance their fertility. As Sudanese we always turn to our heritage as a form of consolation when we feel despair or when our hearts are heavy with sorrow or grief.

At the site of Tumbus you will see carvings on the grey granite stones and it is said that this was the place of a quarry where most of the temple columns were cut before they were transported by boat along the Nile. It is believed that quarry activities began here in the 18th dynasty and that the statue of 'Okji Nunondi’ belongs to King Thutmose III and that the name Tumbus is a distortion of the pharaoh's name.

On our journey to the east of Sudan we visited Kassala city, situated at the heart of Jabal Totil. There we explored the mosque of Al-Sayid al-Hasan where I discovered small bundles of hair tucked into the cracks in the brickwork under the mosque’s windows. I learned that families would visit the mosque with locks of hair from the heads of their newborn children which they would tuck into the mosque’s walls accompanied by supplications for blessings from God. I realised then that even if they were married and had children the heart of devoted followers remained troubled with concerns for the wellbeing offspring.

The story of the founder of the mosque of Al-Sayid al-Hasan is truly remarkable and it is said that he is known as sheikh Abu Jalabiya after one of his miracles. The sheikh is said to have only possessed a single jalabiya which had always fitted him ever since he was a child and that this garment grew as he grew. It is said that the sheikh’s mother knew then that her son was no ordinary child as he was the son of Sayid Mohamed Osman al-Mirgani, the founder of the Khatmiya Sufi order in Sudan.

Through our voyages of discovery in Sudan we came to understand that the Sudanese find profound spiritual peace in their heritage. It connects them to their land and their ancestors, and provides them with strength and hope in their daily life. Every place we visit carries stories and traditions that make us appreciate this homeland more and feel grateful for its legacy that brings us together.

Cover and gallery pictures: The Mosque and Shrine of Elsayed Mohamed al-Hasan Abu Jalabiya, son of the founder of Khatmiyyah Sufi Order © Mohammed Osman, Kassala

I remember when I was at university my friend suddenly cried, “oh, I’m really craving some silt from the river”. At the time, this sounded very strange to me as I was still discovering Sudan and the Sudanese because I was what’s known as ‘shahada Arabia’ - a Sudanese expatriate living in the Arabian Gulf. My knowledge of Sudan was still limited to my village, Ishkit, south of Village 13 in Kassala State and I wasn’t very familiar with Khartoum.

However, after what my friend said, I inadvertently began observing the people around me and tried to understand them and how they loved their country so much they even had a craving for its mud. I admired their deep connection to Sudan, and this feeling became the driving force behind the foundation of ‘Shorrti : Spirit of the place,’ a project which aims to introduce Sudanese people to Sudan and its cultural, environmental and ethnic diversity through events and cultural trips where we explore the different elements of this homeland, including music, heritage, and history.

Shorrti launched in 2016 and since then, we have organized over 54 events in Khartoum and other cities, and have visited over 30 villages and cities in 11 states. In every village or city we visited, more people joined our Shorrti community until eventually, we created our own small village that represented the entire Sudan and dissolved the boundaries of our home towns and cities. We became more connected to the different forms of heritage and to Sudan as a whole and every new person I meet, my understanding of the connection to this land deepens.

I remember that at one particular Shorrti event, I spoke with a man from the Jabal Marra region who told me about an old custom from the time of his ancestors, where they would plant a tree for every newborn and name it after the child. It was as if they were linking their children to the land, creating in them a sense of belonging and connection to their roots. I felt then that the Sudanese people not only love their land, but also carry a special connection to their predecessors buried there. This is reflected in our social and family structures, where we place great importance on the blessing and prayers of our elders. Through our journeys criss-crossing Sudan, I learned that most communities maintain a close connection to their forebears and always have a strong need to receive their blessings.

On our first trip to the Nuri area, specifically to the island of Tarag, there is a mosque and a number of shrines most notably built for the sons of Jaber who were among the first to be taught by Sheikh Ghulam al-Din bin Ayid, founder of the first khalwa in Dongola. However, what caught my attention was the shrine of a sheikh that did not have a dome and which was surrounded by a metal fence with palm fronds attached randomly. When I asked about the reason the fronds were tied there, our guide told me that those who wanted to marry would come here and tie their fronds to the fence and pray to God to grant their wish. This reminded me of the Lovers' Bridge in France where lovers attach padlocks as a symbol of their bond.

As we headed north, accompanied by the melodious sound of the Nile cascading over the sixth to the third cataract, we arrived in Tumbus and the site of 'Okji Nunondi,' a statue lying in the sand. We were told that the statue’s name translates into 'nobleman' or 'knight,' although a more literal translation would be ‘virile man’. This unidentified statue is not only a tourist attraction but has also been a symbol of hope and fertility for thousands of years and has been visited by countless men and women from the region hoping to enhance their fertility. As Sudanese we always turn to our heritage as a form of consolation when we feel despair or when our hearts are heavy with sorrow or grief.

At the site of Tumbus you will see carvings on the grey granite stones and it is said that this was the place of a quarry where most of the temple columns were cut before they were transported by boat along the Nile. It is believed that quarry activities began here in the 18th dynasty and that the statue of 'Okji Nunondi’ belongs to King Thutmose III and that the name Tumbus is a distortion of the pharaoh's name.

On our journey to the east of Sudan we visited Kassala city, situated at the heart of Jabal Totil. There we explored the mosque of Al-Sayid al-Hasan where I discovered small bundles of hair tucked into the cracks in the brickwork under the mosque’s windows. I learned that families would visit the mosque with locks of hair from the heads of their newborn children which they would tuck into the mosque’s walls accompanied by supplications for blessings from God. I realised then that even if they were married and had children the heart of devoted followers remained troubled with concerns for the wellbeing offspring.

The story of the founder of the mosque of Al-Sayid al-Hasan is truly remarkable and it is said that he is known as sheikh Abu Jalabiya after one of his miracles. The sheikh is said to have only possessed a single jalabiya which had always fitted him ever since he was a child and that this garment grew as he grew. It is said that the sheikh’s mother knew then that her son was no ordinary child as he was the son of Sayid Mohamed Osman al-Mirgani, the founder of the Khatmiya Sufi order in Sudan.

Through our voyages of discovery in Sudan we came to understand that the Sudanese find profound spiritual peace in their heritage. It connects them to their land and their ancestors, and provides them with strength and hope in their daily life. Every place we visit carries stories and traditions that make us appreciate this homeland more and feel grateful for its legacy that brings us together.

Cover and gallery pictures: The Mosque and Shrine of Elsayed Mohamed al-Hasan Abu Jalabiya, son of the founder of Khatmiyyah Sufi Order © Mohammed Osman, Kassala

I remember when I was at university my friend suddenly cried, “oh, I’m really craving some silt from the river”. At the time, this sounded very strange to me as I was still discovering Sudan and the Sudanese because I was what’s known as ‘shahada Arabia’ - a Sudanese expatriate living in the Arabian Gulf. My knowledge of Sudan was still limited to my village, Ishkit, south of Village 13 in Kassala State and I wasn’t very familiar with Khartoum.

However, after what my friend said, I inadvertently began observing the people around me and tried to understand them and how they loved their country so much they even had a craving for its mud. I admired their deep connection to Sudan, and this feeling became the driving force behind the foundation of ‘Shorrti : Spirit of the place,’ a project which aims to introduce Sudanese people to Sudan and its cultural, environmental and ethnic diversity through events and cultural trips where we explore the different elements of this homeland, including music, heritage, and history.

Shorrti launched in 2016 and since then, we have organized over 54 events in Khartoum and other cities, and have visited over 30 villages and cities in 11 states. In every village or city we visited, more people joined our Shorrti community until eventually, we created our own small village that represented the entire Sudan and dissolved the boundaries of our home towns and cities. We became more connected to the different forms of heritage and to Sudan as a whole and every new person I meet, my understanding of the connection to this land deepens.

I remember that at one particular Shorrti event, I spoke with a man from the Jabal Marra region who told me about an old custom from the time of his ancestors, where they would plant a tree for every newborn and name it after the child. It was as if they were linking their children to the land, creating in them a sense of belonging and connection to their roots. I felt then that the Sudanese people not only love their land, but also carry a special connection to their predecessors buried there. This is reflected in our social and family structures, where we place great importance on the blessing and prayers of our elders. Through our journeys criss-crossing Sudan, I learned that most communities maintain a close connection to their forebears and always have a strong need to receive their blessings.

On our first trip to the Nuri area, specifically to the island of Tarag, there is a mosque and a number of shrines most notably built for the sons of Jaber who were among the first to be taught by Sheikh Ghulam al-Din bin Ayid, founder of the first khalwa in Dongola. However, what caught my attention was the shrine of a sheikh that did not have a dome and which was surrounded by a metal fence with palm fronds attached randomly. When I asked about the reason the fronds were tied there, our guide told me that those who wanted to marry would come here and tie their fronds to the fence and pray to God to grant their wish. This reminded me of the Lovers' Bridge in France where lovers attach padlocks as a symbol of their bond.

As we headed north, accompanied by the melodious sound of the Nile cascading over the sixth to the third cataract, we arrived in Tumbus and the site of 'Okji Nunondi,' a statue lying in the sand. We were told that the statue’s name translates into 'nobleman' or 'knight,' although a more literal translation would be ‘virile man’. This unidentified statue is not only a tourist attraction but has also been a symbol of hope and fertility for thousands of years and has been visited by countless men and women from the region hoping to enhance their fertility. As Sudanese we always turn to our heritage as a form of consolation when we feel despair or when our hearts are heavy with sorrow or grief.

At the site of Tumbus you will see carvings on the grey granite stones and it is said that this was the place of a quarry where most of the temple columns were cut before they were transported by boat along the Nile. It is believed that quarry activities began here in the 18th dynasty and that the statue of 'Okji Nunondi’ belongs to King Thutmose III and that the name Tumbus is a distortion of the pharaoh's name.

On our journey to the east of Sudan we visited Kassala city, situated at the heart of Jabal Totil. There we explored the mosque of Al-Sayid al-Hasan where I discovered small bundles of hair tucked into the cracks in the brickwork under the mosque’s windows. I learned that families would visit the mosque with locks of hair from the heads of their newborn children which they would tuck into the mosque’s walls accompanied by supplications for blessings from God. I realised then that even if they were married and had children the heart of devoted followers remained troubled with concerns for the wellbeing offspring.

The story of the founder of the mosque of Al-Sayid al-Hasan is truly remarkable and it is said that he is known as sheikh Abu Jalabiya after one of his miracles. The sheikh is said to have only possessed a single jalabiya which had always fitted him ever since he was a child and that this garment grew as he grew. It is said that the sheikh’s mother knew then that her son was no ordinary child as he was the son of Sayid Mohamed Osman al-Mirgani, the founder of the Khatmiya Sufi order in Sudan.