Due North

Travel in all its forms is a tradition as old as time itself. Humans have been on the move forever: for food, for shelter, for safety, for exploration, and for pilgrimage.

/ answered

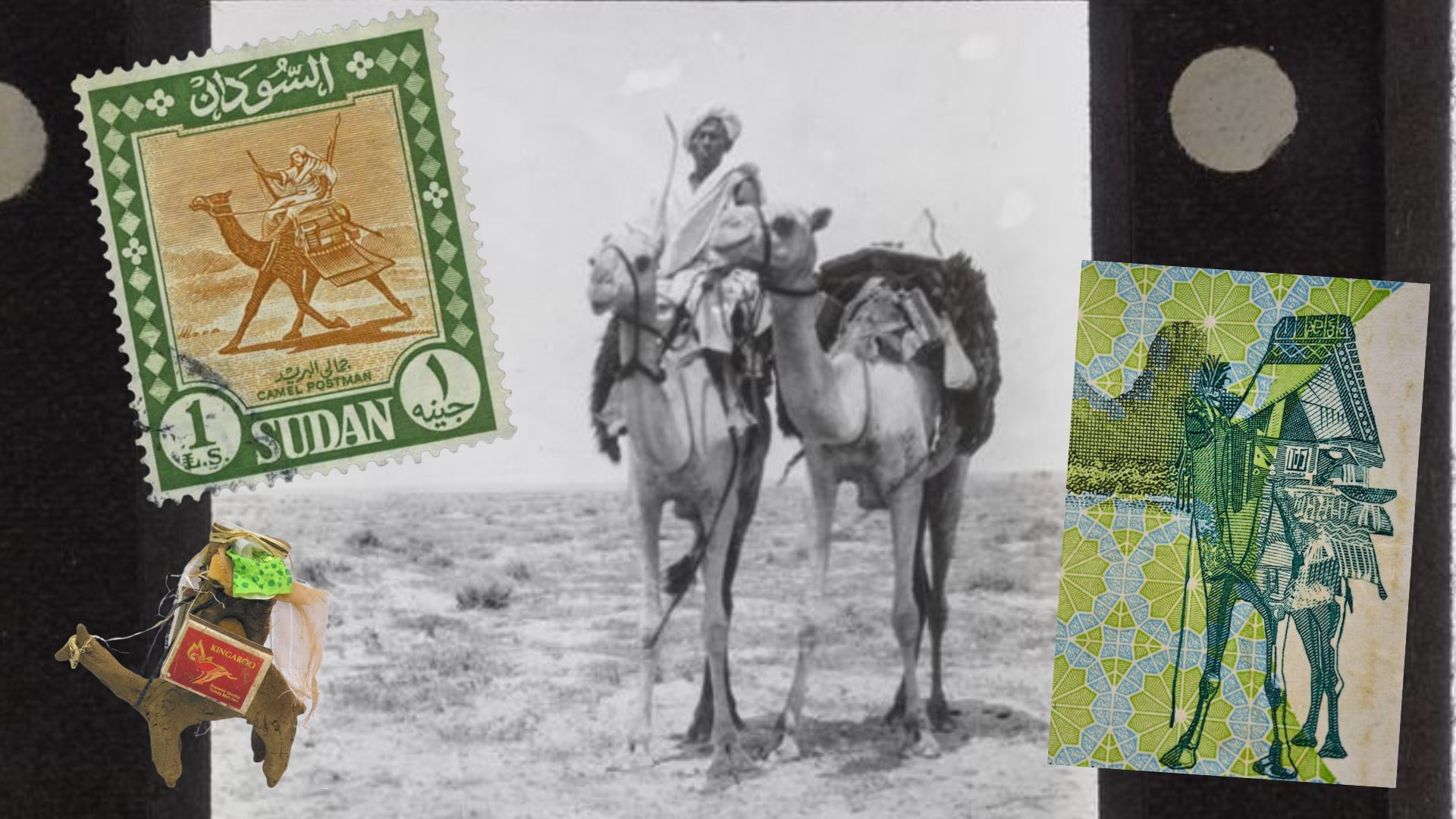

Several years ago, my father was invited by our distant relatives to join them on a unique journey from Sudan to Egypt. This would have been an unremarkable invitation if it hadn’t been for the fact that this journey was on land, through miles of arid desert, on camel back, on a route that has been used for several centuries. The invitation was to accompany the last camel caravan that our tribe the Garareesh would take to the Daraw camel market in Egypt by land through the desert, as a new road had been completed and any future trips would be taken on lorries.

Travel in all its forms is a tradition as old as time itself. Humans have been on the move forever: for food, for shelter, for safety, for exploration, and for pilgrimage. Sometimes they return to their original homes, often home is wherever they put their heads down to rest. Sometimes home is what they are searching for in the first place. This movement could be voluntary, in search of greener pastures, new relationships and economic opportunities. Or it could be forced, fleeing violence or drought, or bound into slavery to be sold. It could be on foot, on animal or on vehicles. Regardless of form or reason, it always holds one thing in common: the expectation – or fear – of something new. Sudan is no different, and its unique location as a gateway to Africa and a bridge to Mecca and Egypt has made it a busy crossroads for centuries. The camel caravans were and continue to be an inseparable part of this fabric, transporting and being transported to different destinations along routes that have been imprinted into the memory of the land and its people.

The magnificence of the camel– a wondrous creation built for the desert – is not limited to its function as a ‘vehicle of the desert’, although this function is no ordinary one. The animal has an unmatched adaptability to the harsh, hot, dry conditions, the ability to go without water or food for up to three weeks, its steady, unfaltering stride for hours on end, and its ability to carry loads many times more than other beasts of labour.

Camels are also favoured for their different products; camel meat is a popular dietary choice in many countries especially Egypt, the hide is exported to Europe to make leather products of the highest quality, and the bones are used to refine sugar, to name just a few. Some camel products are known for their near-mythical healing powers, mostly in their milk, but also strangely in their urine. As a young physician practicing in the Gulf, I witnessed this curious phenomenon first-hand.

A Bedouin baby was diagnosed with infantile leukemia in the hospital I was working in, but her family refused to let her receive any kind of medical treatment. She was brought to the hospital only when she had a fever or diarrhoea. Her diagnosis was confirmed more than once with a bone marrow aspiration – an uncomfortable procedure where a sample is taken from the marrow of the hip bone to give a picture of what blood cells are being produced and in what number. On a follow up visit and repeated test, we were shocked to find that the bone marrow contained no cancerous white blood cells at all. Which was virtually impossible because leukemia doesn’t just disappear. They told us they were giving her a small bottle of camel urine every morning.

Indeed, on more than one follow-up visit, repeated tests showed the same thing: no blood cancer cells. It appeared that the camel urine had some kind of corticosteroid effect that suppressed their production, or maybe even killed them. This effect proved to be temporary, however, and the little girl suffered from a vicious flareup of her illness and sadly passed away two months after her first birthday.

Camel routes between Sudan and Egypt

Desert routes have long been the economic lifeline between Egypt and Sudan, and from Sudan to the rest of Africa. For all its might, the River Nile has played a role of little importance in the context of trade between the two countries it links together, mainly due to the presence of six cataracts that impede movement necessary for trade. Rather, the Nile facilitated the movement of invaders over the years, carrying steamboats of missionaries and soldiers, the most famous of which was the failed expedition sent to rescue Charles Gordon. The desert routes were and continue to be an irreplaceable line along which goods, currency, culture and relationships travel back and forth between Sudan and Egypt, and through which the cultural effect of Sudan on Egypt is evident.

The routes follow the water, crossing the desert along strings of wells scattered in different directions. The three main routes the camel caravans have taken over the centuries between Sudan and Egypt are the Ababda and the Almiheila Routes for caravans coming from the east, and the Way of The Forty for those coming from the west. The biggest route is the Ababda Route named after the Ababda tribe, and dates back to the Funj Dynasty. It originates from Hussein Khalifa Basha’s palace in Eldamar in what is now the River Nile State, and passes through Korosko to Aswan to the Daraw Market in Egypt. This route was great importance for the area and for the different governments of Sudan.

The second route is the Almiheila Route from Alkasinger in the Northern State to Dalgo and has eight wells along the way. The third route is the Way of The Forty or Darb Al Arba’en, with caravans mostly from the Kababeesh tribes of Darfur in the west of Sudan and takes forty days from origin to destination. The Way of the Forty is thought to be named not just for its duration, but also for the number of trips different dervishes had taken along it, and the miracles they were thought to have performed along the way such as crossing the entire length of it on foot.

Up until 1895 there was a fourth route for the camel caravans: the now-extinct Madinab Route, named after the Madinab tribe, who used to travel in enormous caravans of up to two thousand camels to Egypt. Their route was unique in that it had no water wells at all and would have been impossible to take if it weren’t for the tribe’s use of special leather pouches impermeable to water, which they would bury deep in the desert along the way to Egypt, and dig up on the way back. The Madinab, who were famous for their integrity and honesty in trade, were completely wiped out in the Mahdiya wars, taking their caravan secrets with them.

Camel are bought from different tribes and camel markets and grouped together in caravans of growing number, with each group of camels marked with a specific mark that shows who it belongs it. If the camel should die on the way to Egypt, this mark and the bit of skin it is on it cut out and brought back to the owner as proof. The trek through the desert is a difficult one both for the animals and their riders, and not everyone lives to see the end of it. The team accompanying the caravan is made up of seasoned men with a guide familiar with the desert and its dangers, who knows where to find the wells and where to avoid snakes, scorpions and quick-sand.

The caravans travel in groups of up to one hundred camels at a time with a space of two or three days between each batch, as the capacity of the desert wells is limited and can support only so many at a time. They enter Egypt through Aswan and are met at the veterinary centers in Daraw were the camels are inspected and tagged, then loaded onto open-roofed trains to be transported the markets for sale. On the way to Egypt the riders stock up on traditional and Western medicines for themselves and the animals, non-perishable foods and matches, razor blades and needles, and tea and sugar. They arm themselves with rifles for protection from robbers lurking in the dunes. Contraband runners traveling the back routes also carried rifles but smuggled them into Egypt where weapon licenses are difficult to obtain, and smuggled back bullets into Sudan where ammunition can only be purchased through licensed stores. Caravans traveling legally bring back clothes, Egyptian cologne and perfumed soap, water pumps and filters, and molasses and sugar back to Sudan.

Gateway Between East and West

Camel caravans also transport people, livestock and merchandise from the different landlocked countries of Africa through Sudan to the Red Sea. The historic port of Suakin, a main port since as far back as the 10th century, used to be the main gateway between Africa and the East particularly for Muslim pilgrims heading to Mecca, for merchants on both side of the Red Sea, and between Africa and Europe after the Suez Canal was built. Until it was replaced by Port Sudan in the 1920s, the island port received and dispatched hundreds of camel caravans a year. The camels arrived and left the port through different routes: south from Ethiopia, north to Egypt, and north-east to Berber. They carried all sorts of merchandise depending on their origin, the diversity reflecting the diversity of the country and people of Sudan itself: sesame seeds and oil, sorghum, gum Arabic, cotton, honey, butter, coffee, tobacco and rubber. Also, rhinocerous horn, ebony, ostrich feathers, gold, musk, tortoise and seashells, mother-of-pearl and fish. And of course, racing camels, sheep, cattle and slaves.

In Suakin, the legendary Shinnawi Palace provided boarding for the camel caravans, with hundred of rooms on the top, the camel stables on the ground floor, and the massive courtyard that could hold one hundred camels at a time for loading and offloading.

In an interesting coming-to-a-full-circle moment, the detested Turkish governors of Suakin who oversaw the trade facilitated by the camel caravans also collected the taxes, and the caravans carrying these taxes north to the government in Egypt were regularly attacked by celebrated camel-riding highway men from the nomadic Arab tribes of the North. The government showed zero tolerance or mercy to whoever dared to bother these caravans – particularly on the Ababda Route – and punished those they caught in all terrible manners such as beheading and burning alive to make them an example for others.

The camel caravans in A Mouth Full of Salt

In my novel A Mouth Full of Salt, a young man from a village in North Sudan travels with the camel caravans to Egypt on the Ababda Route, which is also the route my own relatives – the Garareesh tribe – took up until the road was built, and which my father was invited to join them on but could not due to work commitments. While the camel trade is still quite alive and kicking, changing times have dictated changing traditions. The days’ long journey is no longer trekked through the desert. Instead, camels are now loaded onto lorries and driven along the new road to Egypt through the Argeen border. This trip takes just eight hours from Dongola to the Daraw market. The camels and their carers arrive a little dusty but otherwise in full strength and luster. Camels are still exported in the thousands not only for their meat and other products, but also for camel racing and beauty pageants.

The camel train made its way into my novel in bits and pieces. The camel trade with all its glory and income does not exist everywhere in Sudan. Even in the Northern State only specific areas and tribes still hold onto this tradition and are able to breed camels and trade in them. Camels are not easy beings to be tamed and dominated, and some breeds are known for their ferocity. There are all sorts of stories about what goes in the mind of a camel concerning humans they deem undesirable. I will always remember a story I was told about a herder who beat and insulted his camel, and when they were out in the desert when night, the camel (allegedly) waited until everyone was asleep then quietly moved over to wear the man was and sat on him. I find it a little troubling that after everything I learned about camels, I am still unable to tell if this story was true or made up.

This article was written with the valuable expertise and experience of Prof. Abdelrahim M Salih, professor of Anthropology and Linguistics at American University

Several years ago, my father was invited by our distant relatives to join them on a unique journey from Sudan to Egypt. This would have been an unremarkable invitation if it hadn’t been for the fact that this journey was on land, through miles of arid desert, on camel back, on a route that has been used for several centuries. The invitation was to accompany the last camel caravan that our tribe the Garareesh would take to the Daraw camel market in Egypt by land through the desert, as a new road had been completed and any future trips would be taken on lorries.

Travel in all its forms is a tradition as old as time itself. Humans have been on the move forever: for food, for shelter, for safety, for exploration, and for pilgrimage. Sometimes they return to their original homes, often home is wherever they put their heads down to rest. Sometimes home is what they are searching for in the first place. This movement could be voluntary, in search of greener pastures, new relationships and economic opportunities. Or it could be forced, fleeing violence or drought, or bound into slavery to be sold. It could be on foot, on animal or on vehicles. Regardless of form or reason, it always holds one thing in common: the expectation – or fear – of something new. Sudan is no different, and its unique location as a gateway to Africa and a bridge to Mecca and Egypt has made it a busy crossroads for centuries. The camel caravans were and continue to be an inseparable part of this fabric, transporting and being transported to different destinations along routes that have been imprinted into the memory of the land and its people.

The magnificence of the camel– a wondrous creation built for the desert – is not limited to its function as a ‘vehicle of the desert’, although this function is no ordinary one. The animal has an unmatched adaptability to the harsh, hot, dry conditions, the ability to go without water or food for up to three weeks, its steady, unfaltering stride for hours on end, and its ability to carry loads many times more than other beasts of labour.

Camels are also favoured for their different products; camel meat is a popular dietary choice in many countries especially Egypt, the hide is exported to Europe to make leather products of the highest quality, and the bones are used to refine sugar, to name just a few. Some camel products are known for their near-mythical healing powers, mostly in their milk, but also strangely in their urine. As a young physician practicing in the Gulf, I witnessed this curious phenomenon first-hand.

A Bedouin baby was diagnosed with infantile leukemia in the hospital I was working in, but her family refused to let her receive any kind of medical treatment. She was brought to the hospital only when she had a fever or diarrhoea. Her diagnosis was confirmed more than once with a bone marrow aspiration – an uncomfortable procedure where a sample is taken from the marrow of the hip bone to give a picture of what blood cells are being produced and in what number. On a follow up visit and repeated test, we were shocked to find that the bone marrow contained no cancerous white blood cells at all. Which was virtually impossible because leukemia doesn’t just disappear. They told us they were giving her a small bottle of camel urine every morning.

Indeed, on more than one follow-up visit, repeated tests showed the same thing: no blood cancer cells. It appeared that the camel urine had some kind of corticosteroid effect that suppressed their production, or maybe even killed them. This effect proved to be temporary, however, and the little girl suffered from a vicious flareup of her illness and sadly passed away two months after her first birthday.

Camel routes between Sudan and Egypt

Desert routes have long been the economic lifeline between Egypt and Sudan, and from Sudan to the rest of Africa. For all its might, the River Nile has played a role of little importance in the context of trade between the two countries it links together, mainly due to the presence of six cataracts that impede movement necessary for trade. Rather, the Nile facilitated the movement of invaders over the years, carrying steamboats of missionaries and soldiers, the most famous of which was the failed expedition sent to rescue Charles Gordon. The desert routes were and continue to be an irreplaceable line along which goods, currency, culture and relationships travel back and forth between Sudan and Egypt, and through which the cultural effect of Sudan on Egypt is evident.

The routes follow the water, crossing the desert along strings of wells scattered in different directions. The three main routes the camel caravans have taken over the centuries between Sudan and Egypt are the Ababda and the Almiheila Routes for caravans coming from the east, and the Way of The Forty for those coming from the west. The biggest route is the Ababda Route named after the Ababda tribe, and dates back to the Funj Dynasty. It originates from Hussein Khalifa Basha’s palace in Eldamar in what is now the River Nile State, and passes through Korosko to Aswan to the Daraw Market in Egypt. This route was great importance for the area and for the different governments of Sudan.

The second route is the Almiheila Route from Alkasinger in the Northern State to Dalgo and has eight wells along the way. The third route is the Way of The Forty or Darb Al Arba’en, with caravans mostly from the Kababeesh tribes of Darfur in the west of Sudan and takes forty days from origin to destination. The Way of the Forty is thought to be named not just for its duration, but also for the number of trips different dervishes had taken along it, and the miracles they were thought to have performed along the way such as crossing the entire length of it on foot.

Up until 1895 there was a fourth route for the camel caravans: the now-extinct Madinab Route, named after the Madinab tribe, who used to travel in enormous caravans of up to two thousand camels to Egypt. Their route was unique in that it had no water wells at all and would have been impossible to take if it weren’t for the tribe’s use of special leather pouches impermeable to water, which they would bury deep in the desert along the way to Egypt, and dig up on the way back. The Madinab, who were famous for their integrity and honesty in trade, were completely wiped out in the Mahdiya wars, taking their caravan secrets with them.

Camel are bought from different tribes and camel markets and grouped together in caravans of growing number, with each group of camels marked with a specific mark that shows who it belongs it. If the camel should die on the way to Egypt, this mark and the bit of skin it is on it cut out and brought back to the owner as proof. The trek through the desert is a difficult one both for the animals and their riders, and not everyone lives to see the end of it. The team accompanying the caravan is made up of seasoned men with a guide familiar with the desert and its dangers, who knows where to find the wells and where to avoid snakes, scorpions and quick-sand.

The caravans travel in groups of up to one hundred camels at a time with a space of two or three days between each batch, as the capacity of the desert wells is limited and can support only so many at a time. They enter Egypt through Aswan and are met at the veterinary centers in Daraw were the camels are inspected and tagged, then loaded onto open-roofed trains to be transported the markets for sale. On the way to Egypt the riders stock up on traditional and Western medicines for themselves and the animals, non-perishable foods and matches, razor blades and needles, and tea and sugar. They arm themselves with rifles for protection from robbers lurking in the dunes. Contraband runners traveling the back routes also carried rifles but smuggled them into Egypt where weapon licenses are difficult to obtain, and smuggled back bullets into Sudan where ammunition can only be purchased through licensed stores. Caravans traveling legally bring back clothes, Egyptian cologne and perfumed soap, water pumps and filters, and molasses and sugar back to Sudan.

Gateway Between East and West

Camel caravans also transport people, livestock and merchandise from the different landlocked countries of Africa through Sudan to the Red Sea. The historic port of Suakin, a main port since as far back as the 10th century, used to be the main gateway between Africa and the East particularly for Muslim pilgrims heading to Mecca, for merchants on both side of the Red Sea, and between Africa and Europe after the Suez Canal was built. Until it was replaced by Port Sudan in the 1920s, the island port received and dispatched hundreds of camel caravans a year. The camels arrived and left the port through different routes: south from Ethiopia, north to Egypt, and north-east to Berber. They carried all sorts of merchandise depending on their origin, the diversity reflecting the diversity of the country and people of Sudan itself: sesame seeds and oil, sorghum, gum Arabic, cotton, honey, butter, coffee, tobacco and rubber. Also, rhinocerous horn, ebony, ostrich feathers, gold, musk, tortoise and seashells, mother-of-pearl and fish. And of course, racing camels, sheep, cattle and slaves.

In Suakin, the legendary Shinnawi Palace provided boarding for the camel caravans, with hundred of rooms on the top, the camel stables on the ground floor, and the massive courtyard that could hold one hundred camels at a time for loading and offloading.

In an interesting coming-to-a-full-circle moment, the detested Turkish governors of Suakin who oversaw the trade facilitated by the camel caravans also collected the taxes, and the caravans carrying these taxes north to the government in Egypt were regularly attacked by celebrated camel-riding highway men from the nomadic Arab tribes of the North. The government showed zero tolerance or mercy to whoever dared to bother these caravans – particularly on the Ababda Route – and punished those they caught in all terrible manners such as beheading and burning alive to make them an example for others.

The camel caravans in A Mouth Full of Salt

In my novel A Mouth Full of Salt, a young man from a village in North Sudan travels with the camel caravans to Egypt on the Ababda Route, which is also the route my own relatives – the Garareesh tribe – took up until the road was built, and which my father was invited to join them on but could not due to work commitments. While the camel trade is still quite alive and kicking, changing times have dictated changing traditions. The days’ long journey is no longer trekked through the desert. Instead, camels are now loaded onto lorries and driven along the new road to Egypt through the Argeen border. This trip takes just eight hours from Dongola to the Daraw market. The camels and their carers arrive a little dusty but otherwise in full strength and luster. Camels are still exported in the thousands not only for their meat and other products, but also for camel racing and beauty pageants.

The camel train made its way into my novel in bits and pieces. The camel trade with all its glory and income does not exist everywhere in Sudan. Even in the Northern State only specific areas and tribes still hold onto this tradition and are able to breed camels and trade in them. Camels are not easy beings to be tamed and dominated, and some breeds are known for their ferocity. There are all sorts of stories about what goes in the mind of a camel concerning humans they deem undesirable. I will always remember a story I was told about a herder who beat and insulted his camel, and when they were out in the desert when night, the camel (allegedly) waited until everyone was asleep then quietly moved over to wear the man was and sat on him. I find it a little troubling that after everything I learned about camels, I am still unable to tell if this story was true or made up.

This article was written with the valuable expertise and experience of Prof. Abdelrahim M Salih, professor of Anthropology and Linguistics at American University

.svg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)