Moving Cities

Both people and places move. Concepts of home, land and stability are present in both settled and nomadic lifestyles and as such, both can be subject to displacement. This section looks at the intersection of these concepts.

Al-Sibyan Magazine

Al-Sibyan Magazine

Al-Sibyan Magazine was launched in 1946 at the publishing department of the Institute of Education in Bakht al-Ruda. Managed by Awad Sati, the magazine educated its readers through the meaningful topics and stories it published, and included the wise words in Uncle Saror’s column at the beginning of every issue. Al-Sibyan magazine has always been a favourite with Sudanese children and has a special place in the hearts of its friends and readers.

Al-Sibyan’s friends

Al-Sibyan’s readership ranged from those who read it weekly or those who waited to consume it every month to even those who found dusty old issues stored at home and enjoyed reading all the issues consecutively.

The circle of Al-Sibyan’s friends was not limited to Khartoum, with the magazine reaching friends all around the country’s cities and rural areas. Aunt Zahra's column, ‘Hello Al-Sibyan’s Friends’, included correspondences from children who wrote to greet her, share a photo from their summer holiday, tell a story or joke or to complain that their contributions to the magazine had not been published. Ramadan from Karima town and Al-Tijani from Nyala wrote to Aunt Zahra to share photographs of themselves, while Nabawiya from Al-Diyum wrote to enquire about the magazine’s periodic competition, Suad from Burri shared a paragraph about her hobbies and Makki from Kadugli wrote in just to say hello. The ‘Meeting Friends’ sections of the magazine published anecdotes shared by friends from Omdurman, Kassala, Al-Rahad, Al-Junaid and Shendi.

City themes in the magazine

It is worth mentioning that in addition to the magazine's friends being located across Sudan, Al-Sibyan’s content was also varied and reflected this range and diversity, and as such, every issue contained a story or topic dealing with one of Sudan's districts or cities. For example, Ihsan Al Mubarak wrote about her journey from Khartoum to Kassala, passing through Madani, Gedaref and New Halfa to reach Durrat Al-Sharq in eastern Sudan. Ihsan describes the city's beautiful nature, represented by the Taka Mountains and the fresh water spring of Toteel, and then the city's market, which contained products that were reflective of the rich resources for which the city is famous, such as ropes from palm fronds, daggers, swords, and items of pottery. She then touches on the factories in Kassala and lists some of the factories that produce many local products that are exported abroad. In other issues, we find similar articles about Juba, Kadugli and Kosti and many other cities. The importance of these articles about different cities is not only to describe and inform its readers about them, but to also broaden the children’s perception of a city extending to go beyond their immediate surroundings. The connection between ‘Friends of Al-Sibyan’ and the various cities of Sudan is more than just an exercise of listing city names, it leads to a deeper knowledge of the nature of each city and its inhabitants.

All pictures in this gallery are from Sudan Memory website

Al-Sibyan Magazine was launched in 1946 at the publishing department of the Institute of Education in Bakht al-Ruda. Managed by Awad Sati, the magazine educated its readers through the meaningful topics and stories it published, and included the wise words in Uncle Saror’s column at the beginning of every issue. Al-Sibyan magazine has always been a favourite with Sudanese children and has a special place in the hearts of its friends and readers.

Al-Sibyan’s friends

Al-Sibyan’s readership ranged from those who read it weekly or those who waited to consume it every month to even those who found dusty old issues stored at home and enjoyed reading all the issues consecutively.

The circle of Al-Sibyan’s friends was not limited to Khartoum, with the magazine reaching friends all around the country’s cities and rural areas. Aunt Zahra's column, ‘Hello Al-Sibyan’s Friends’, included correspondences from children who wrote to greet her, share a photo from their summer holiday, tell a story or joke or to complain that their contributions to the magazine had not been published. Ramadan from Karima town and Al-Tijani from Nyala wrote to Aunt Zahra to share photographs of themselves, while Nabawiya from Al-Diyum wrote to enquire about the magazine’s periodic competition, Suad from Burri shared a paragraph about her hobbies and Makki from Kadugli wrote in just to say hello. The ‘Meeting Friends’ sections of the magazine published anecdotes shared by friends from Omdurman, Kassala, Al-Rahad, Al-Junaid and Shendi.

City themes in the magazine

It is worth mentioning that in addition to the magazine's friends being located across Sudan, Al-Sibyan’s content was also varied and reflected this range and diversity, and as such, every issue contained a story or topic dealing with one of Sudan's districts or cities. For example, Ihsan Al Mubarak wrote about her journey from Khartoum to Kassala, passing through Madani, Gedaref and New Halfa to reach Durrat Al-Sharq in eastern Sudan. Ihsan describes the city's beautiful nature, represented by the Taka Mountains and the fresh water spring of Toteel, and then the city's market, which contained products that were reflective of the rich resources for which the city is famous, such as ropes from palm fronds, daggers, swords, and items of pottery. She then touches on the factories in Kassala and lists some of the factories that produce many local products that are exported abroad. In other issues, we find similar articles about Juba, Kadugli and Kosti and many other cities. The importance of these articles about different cities is not only to describe and inform its readers about them, but to also broaden the children’s perception of a city extending to go beyond their immediate surroundings. The connection between ‘Friends of Al-Sibyan’ and the various cities of Sudan is more than just an exercise of listing city names, it leads to a deeper knowledge of the nature of each city and its inhabitants.

All pictures in this gallery are from Sudan Memory website

Al-Sibyan Magazine was launched in 1946 at the publishing department of the Institute of Education in Bakht al-Ruda. Managed by Awad Sati, the magazine educated its readers through the meaningful topics and stories it published, and included the wise words in Uncle Saror’s column at the beginning of every issue. Al-Sibyan magazine has always been a favourite with Sudanese children and has a special place in the hearts of its friends and readers.

Al-Sibyan’s friends

Al-Sibyan’s readership ranged from those who read it weekly or those who waited to consume it every month to even those who found dusty old issues stored at home and enjoyed reading all the issues consecutively.

The circle of Al-Sibyan’s friends was not limited to Khartoum, with the magazine reaching friends all around the country’s cities and rural areas. Aunt Zahra's column, ‘Hello Al-Sibyan’s Friends’, included correspondences from children who wrote to greet her, share a photo from their summer holiday, tell a story or joke or to complain that their contributions to the magazine had not been published. Ramadan from Karima town and Al-Tijani from Nyala wrote to Aunt Zahra to share photographs of themselves, while Nabawiya from Al-Diyum wrote to enquire about the magazine’s periodic competition, Suad from Burri shared a paragraph about her hobbies and Makki from Kadugli wrote in just to say hello. The ‘Meeting Friends’ sections of the magazine published anecdotes shared by friends from Omdurman, Kassala, Al-Rahad, Al-Junaid and Shendi.

City themes in the magazine

It is worth mentioning that in addition to the magazine's friends being located across Sudan, Al-Sibyan’s content was also varied and reflected this range and diversity, and as such, every issue contained a story or topic dealing with one of Sudan's districts or cities. For example, Ihsan Al Mubarak wrote about her journey from Khartoum to Kassala, passing through Madani, Gedaref and New Halfa to reach Durrat Al-Sharq in eastern Sudan. Ihsan describes the city's beautiful nature, represented by the Taka Mountains and the fresh water spring of Toteel, and then the city's market, which contained products that were reflective of the rich resources for which the city is famous, such as ropes from palm fronds, daggers, swords, and items of pottery. She then touches on the factories in Kassala and lists some of the factories that produce many local products that are exported abroad. In other issues, we find similar articles about Juba, Kadugli and Kosti and many other cities. The importance of these articles about different cities is not only to describe and inform its readers about them, but to also broaden the children’s perception of a city extending to go beyond their immediate surroundings. The connection between ‘Friends of Al-Sibyan’ and the various cities of Sudan is more than just an exercise of listing city names, it leads to a deeper knowledge of the nature of each city and its inhabitants.

All pictures in this gallery are from Sudan Memory website

City within a city

City within a city

Recently, and while looking through the tens of pictures I have stored on my laptop, I came across a folder of photos reminding me of the glimpses of the lives my ‘Habesha’ friends had in Khartoum. The pictures were taken during various visits to friends’ homes in Al-Jirayf and Al-Sahafa, both neighbourhoods of Khartoum known for their large populations of Ethiopian and Eritrean migrants. I remember the sense of a city within a city that I had as we walked around Al-Jirayf taking in all the shops and restaurants where Ethiopian and Eritrean food and clothes, perfumes and hair products were on sale with large signs in Amharic displayed across shop doorways. The place felt like a community was being recreated, made coherent through the cultural material goods and objects that were on display and for sale in their new, often temporary home.

Most of the Ethiopians and Eritreans I have met, both inside and outside Sudan, have a fondness for the country; they are descended from the same tribes along shared borders; have passed through the country on their perilous journey to a better life in Europe or America; or they, or other family members, have settled in Khartoum. And while they got on well with ordinary Sudanese people, my friends would often complain about their constant battle with the absurd, and often exploitative encounters they had with the Sudanese police and authorities on the pretext of enforcing immigration rules.

I remembered the Ethiopian Orthodox church in Khartoum 2 whose bells and chanting went on for hours and the crowds of worshippers in their bright white dresses, trouser suits and shawls trooping towards it, children in hand. The Ethiopian street vendors lining the street outside the church with their grains, flours and spices and the many other colourful items laid out on the ground in front of them. And the more austere Protestant Church with their upbeat hymns, a building they shared with Sudanese Protestants from the Nuba mountains.

This was an immigrant population that had created around it a space that was reminiscent of home but which was open to their Sudanese hosts to sample and experience it. Zighni and injera were popularised while the Ethiopian coffee making ceremony, with all the paraphernalia of incense burning and popcorn making and the stools, low table and small coffee cups became a familiar sight.

Since the war, many of the Ethiopians and Eritreans who lived in Al-Jirayf and Al-Sahafa have been forced to leave, either to safer towns like many of the Sudanese, or back to their countries.

The idea of a city within a city, where people recreate ‘their homeland’ in a host country and attempt to practice their cultural heritage is a fluid process. It does not exist in isolation or to the exclusion of others because after all, they are a stone’s throw from their hosts and must adapt and find ways to live alongside them and within the host society. These cities within cities are a source of comfort, to remind them of who they are and where they are from, emphasising the difference between them and the host country but also the similarities and what can be shared.

Cover Picture © Sara Elnagar, showing Ethiopian, Eritrean Cemetary in Al-Sahafa

Recently, and while looking through the tens of pictures I have stored on my laptop, I came across a folder of photos reminding me of the glimpses of the lives my ‘Habesha’ friends had in Khartoum. The pictures were taken during various visits to friends’ homes in Al-Jirayf and Al-Sahafa, both neighbourhoods of Khartoum known for their large populations of Ethiopian and Eritrean migrants. I remember the sense of a city within a city that I had as we walked around Al-Jirayf taking in all the shops and restaurants where Ethiopian and Eritrean food and clothes, perfumes and hair products were on sale with large signs in Amharic displayed across shop doorways. The place felt like a community was being recreated, made coherent through the cultural material goods and objects that were on display and for sale in their new, often temporary home.

Most of the Ethiopians and Eritreans I have met, both inside and outside Sudan, have a fondness for the country; they are descended from the same tribes along shared borders; have passed through the country on their perilous journey to a better life in Europe or America; or they, or other family members, have settled in Khartoum. And while they got on well with ordinary Sudanese people, my friends would often complain about their constant battle with the absurd, and often exploitative encounters they had with the Sudanese police and authorities on the pretext of enforcing immigration rules.

I remembered the Ethiopian Orthodox church in Khartoum 2 whose bells and chanting went on for hours and the crowds of worshippers in their bright white dresses, trouser suits and shawls trooping towards it, children in hand. The Ethiopian street vendors lining the street outside the church with their grains, flours and spices and the many other colourful items laid out on the ground in front of them. And the more austere Protestant Church with their upbeat hymns, a building they shared with Sudanese Protestants from the Nuba mountains.

This was an immigrant population that had created around it a space that was reminiscent of home but which was open to their Sudanese hosts to sample and experience it. Zighni and injera were popularised while the Ethiopian coffee making ceremony, with all the paraphernalia of incense burning and popcorn making and the stools, low table and small coffee cups became a familiar sight.

Since the war, many of the Ethiopians and Eritreans who lived in Al-Jirayf and Al-Sahafa have been forced to leave, either to safer towns like many of the Sudanese, or back to their countries.

The idea of a city within a city, where people recreate ‘their homeland’ in a host country and attempt to practice their cultural heritage is a fluid process. It does not exist in isolation or to the exclusion of others because after all, they are a stone’s throw from their hosts and must adapt and find ways to live alongside them and within the host society. These cities within cities are a source of comfort, to remind them of who they are and where they are from, emphasising the difference between them and the host country but also the similarities and what can be shared.

Cover Picture © Sara Elnagar, showing Ethiopian, Eritrean Cemetary in Al-Sahafa

Recently, and while looking through the tens of pictures I have stored on my laptop, I came across a folder of photos reminding me of the glimpses of the lives my ‘Habesha’ friends had in Khartoum. The pictures were taken during various visits to friends’ homes in Al-Jirayf and Al-Sahafa, both neighbourhoods of Khartoum known for their large populations of Ethiopian and Eritrean migrants. I remember the sense of a city within a city that I had as we walked around Al-Jirayf taking in all the shops and restaurants where Ethiopian and Eritrean food and clothes, perfumes and hair products were on sale with large signs in Amharic displayed across shop doorways. The place felt like a community was being recreated, made coherent through the cultural material goods and objects that were on display and for sale in their new, often temporary home.

Most of the Ethiopians and Eritreans I have met, both inside and outside Sudan, have a fondness for the country; they are descended from the same tribes along shared borders; have passed through the country on their perilous journey to a better life in Europe or America; or they, or other family members, have settled in Khartoum. And while they got on well with ordinary Sudanese people, my friends would often complain about their constant battle with the absurd, and often exploitative encounters they had with the Sudanese police and authorities on the pretext of enforcing immigration rules.

I remembered the Ethiopian Orthodox church in Khartoum 2 whose bells and chanting went on for hours and the crowds of worshippers in their bright white dresses, trouser suits and shawls trooping towards it, children in hand. The Ethiopian street vendors lining the street outside the church with their grains, flours and spices and the many other colourful items laid out on the ground in front of them. And the more austere Protestant Church with their upbeat hymns, a building they shared with Sudanese Protestants from the Nuba mountains.

This was an immigrant population that had created around it a space that was reminiscent of home but which was open to their Sudanese hosts to sample and experience it. Zighni and injera were popularised while the Ethiopian coffee making ceremony, with all the paraphernalia of incense burning and popcorn making and the stools, low table and small coffee cups became a familiar sight.

Since the war, many of the Ethiopians and Eritreans who lived in Al-Jirayf and Al-Sahafa have been forced to leave, either to safer towns like many of the Sudanese, or back to their countries.

The idea of a city within a city, where people recreate ‘their homeland’ in a host country and attempt to practice their cultural heritage is a fluid process. It does not exist in isolation or to the exclusion of others because after all, they are a stone’s throw from their hosts and must adapt and find ways to live alongside them and within the host society. These cities within cities are a source of comfort, to remind them of who they are and where they are from, emphasising the difference between them and the host country but also the similarities and what can be shared.

Cover Picture © Sara Elnagar, showing Ethiopian, Eritrean Cemetary in Al-Sahafa

Habitat of Kordofan

.jpeg)

Habitat of Kordofan

The population of Kordofan is a mixture of diverse ethnicities and tribes. The history of the demographic geography of Kordofan begins with the entry of various residents into the region who came from the west via Libya and Darfur and from the east via the Nile. They settled in this land and mixed with the native inhabitants of the Abbala, Bara, Nuba and other tribes. The city of El Obeid also witnessed another demographic change in the nineteenth century during the Turkish era, with the influx of foreign communities such as Greeks, Levantines, Copts, Indians, and Armenians.

From an economic standpoint, the people of Kordofan can be divided into two parts:

The settlers residing in cities, villages, and neighborhoods (Hilla). They are part of the urban labor, and work in agriculture, gardening, and animal husbandry.

The nomads/pastorals are animal herders such as camels, and they are the ones who specialize in raising and caring for camels. The men travel on bare camels and the women ride in howdahs. There are also the Baggara tribes, which are the tribes who specialize in raising and caring for cows. Men ride bulls, horses, and donkeys, and women also ride howdah-ed bulls. Nomads use several means to transport their food supplies, household equipment, and even the people used to build temporary homes.

The city of El Obeid has changed and developed over the years. The neighborhoods of the old city were fenced pieces of land, inside each corral there was a group of Quttia “huts”, karnaks “kitchens”, Rakuba “open verandas”, and other parts of the house. The city was divided into five areas around the creek that ran in the middle of the city. The current formation of the city occurred during the various periods of rule and colonialism.

The population of Kordofan is a mixture of diverse ethnicities and tribes. The history of the demographic geography of Kordofan begins with the entry of various residents into the region who came from the west via Libya and Darfur and from the east via the Nile. They settled in this land and mixed with the native inhabitants of the Abbala, Bara, Nuba and other tribes. The city of El Obeid also witnessed another demographic change in the nineteenth century during the Turkish era, with the influx of foreign communities such as Greeks, Levantines, Copts, Indians, and Armenians.

From an economic standpoint, the people of Kordofan can be divided into two parts:

The settlers residing in cities, villages, and neighborhoods (Hilla). They are part of the urban labor, and work in agriculture, gardening, and animal husbandry.

The nomads/pastorals are animal herders such as camels, and they are the ones who specialize in raising and caring for camels. The men travel on bare camels and the women ride in howdahs. There are also the Baggara tribes, which are the tribes who specialize in raising and caring for cows. Men ride bulls, horses, and donkeys, and women also ride howdah-ed bulls. Nomads use several means to transport their food supplies, household equipment, and even the people used to build temporary homes.

The city of El Obeid has changed and developed over the years. The neighborhoods of the old city were fenced pieces of land, inside each corral there was a group of Quttia “huts”, karnaks “kitchens”, Rakuba “open verandas”, and other parts of the house. The city was divided into five areas around the creek that ran in the middle of the city. The current formation of the city occurred during the various periods of rule and colonialism.

.jpeg)

The population of Kordofan is a mixture of diverse ethnicities and tribes. The history of the demographic geography of Kordofan begins with the entry of various residents into the region who came from the west via Libya and Darfur and from the east via the Nile. They settled in this land and mixed with the native inhabitants of the Abbala, Bara, Nuba and other tribes. The city of El Obeid also witnessed another demographic change in the nineteenth century during the Turkish era, with the influx of foreign communities such as Greeks, Levantines, Copts, Indians, and Armenians.

From an economic standpoint, the people of Kordofan can be divided into two parts:

The settlers residing in cities, villages, and neighborhoods (Hilla). They are part of the urban labor, and work in agriculture, gardening, and animal husbandry.

The nomads/pastorals are animal herders such as camels, and they are the ones who specialize in raising and caring for camels. The men travel on bare camels and the women ride in howdahs. There are also the Baggara tribes, which are the tribes who specialize in raising and caring for cows. Men ride bulls, horses, and donkeys, and women also ride howdah-ed bulls. Nomads use several means to transport their food supplies, household equipment, and even the people used to build temporary homes.

The city of El Obeid has changed and developed over the years. The neighborhoods of the old city were fenced pieces of land, inside each corral there was a group of Quttia “huts”, karnaks “kitchens”, Rakuba “open verandas”, and other parts of the house. The city was divided into five areas around the creek that ran in the middle of the city. The current formation of the city occurred during the various periods of rule and colonialism.

The moving land

.jpeg)

The moving land

What does a city mean? When we asked a resident of Old Haj Yousif if he considered his neighborhood to be a city, he said yes. We asked why, and he said it was because foreigners were now moving into the neighborhood. Haj Yousif was an urban village to the north of Khartoum that was absorbed by the city's urban expansion. I asked the same question to a resident of Alshigailab, another village that the city stretched into in recent years. His answer was that the changing livelihoods of the residents and the replanning of their village made it a city. Governments also have their own ways of deciding what a city is. Usually, the number of residents in one area of land is the key indicator; sometimes it is the types and scale of services, which are also determined by the population density of a particular geographical area. Services are placed to serve a specific catchment area. However, a unanimous understanding of a city is that it’s a fixed piece of land that expands, grows, and changes for various reasons, including sociopolitical changes.

The events of 2024 in Sudan are game-changing. By April 2024, exactly one year after the beginning of the war, over ten million people had been displaced, approximately a quarter of Sudan's entire population, according to IOM estimates. This is the population size of a megacity or twenty or so regular-sized cities. The use of a city as a measurement is critical here, as for cities to exist and be sustained, they require a certain level of infrastructure, capacity, governance, food production, and basic services. Over 80% of the displaced individuals are still within Sudan, integrating into other already extremely undeveloped villages, towns, and small cities. They are straining the capacity of these settlements and threatening the entire country with the largest humanitarian crisis in the world, and a critical state of food security and famine.

Now let's take a different angle and look at the same issue. The majority of the displaced population are urban residents fleeing three of the largest cities in Sudan: Khartoum, Wadi Madani, and Nyala. However, the largest population of Sudan is actually rural, such as farmers and pastoralists. These communities have also been affected by the conflict as the war has disrupted their livelihoods, lifestyles, and routes of movement. However, a comparison between nomadic lifestyle, which involves voluntary movement, and conflict-induced movement is worth mentioning.

Nomads move in large numbers, often accompanied by their livestock, which can cover the area of small settlements. Like the current displaced people, the nomadic populations can also be considered moving pieces of land. Pastoralists have been roaming the earth for centuries, if not millennia. They function to a large extent like a regular fixed settlement, growing and shrinking in size. They have full moving services catered to this number of people and animals, even though the type of required infrastructure for nomadism is obviously different from a settled settlement. They still have medical and environmental experts, routes of movement, housing, and governance.

Communal and customary land laws are a very complicated issue, so it would not be feasible to include them in this writing. However, the land required to house all the needs of nomads will always be there. If we take land use or the right to occupy land for certain amounts of time as a form of temporary ownership, this seasonal ownership that occurs every year for years creates boundaries of customary agreements and encroachments. The use in question and how resources are shared are some of the many originating causes of disagreements. But these frameworks also hold potential answers to current issues. Borrowing frameworks from these lifestyles can help tackle current issues of displacement. How do cities move? What could make a city on four legs? What if people continue to move? How can urban experts learn from the rural?

What does a city mean? When we asked a resident of Old Haj Yousif if he considered his neighborhood to be a city, he said yes. We asked why, and he said it was because foreigners were now moving into the neighborhood. Haj Yousif was an urban village to the north of Khartoum that was absorbed by the city's urban expansion. I asked the same question to a resident of Alshigailab, another village that the city stretched into in recent years. His answer was that the changing livelihoods of the residents and the replanning of their village made it a city. Governments also have their own ways of deciding what a city is. Usually, the number of residents in one area of land is the key indicator; sometimes it is the types and scale of services, which are also determined by the population density of a particular geographical area. Services are placed to serve a specific catchment area. However, a unanimous understanding of a city is that it’s a fixed piece of land that expands, grows, and changes for various reasons, including sociopolitical changes.

The events of 2024 in Sudan are game-changing. By April 2024, exactly one year after the beginning of the war, over ten million people had been displaced, approximately a quarter of Sudan's entire population, according to IOM estimates. This is the population size of a megacity or twenty or so regular-sized cities. The use of a city as a measurement is critical here, as for cities to exist and be sustained, they require a certain level of infrastructure, capacity, governance, food production, and basic services. Over 80% of the displaced individuals are still within Sudan, integrating into other already extremely undeveloped villages, towns, and small cities. They are straining the capacity of these settlements and threatening the entire country with the largest humanitarian crisis in the world, and a critical state of food security and famine.

Now let's take a different angle and look at the same issue. The majority of the displaced population are urban residents fleeing three of the largest cities in Sudan: Khartoum, Wadi Madani, and Nyala. However, the largest population of Sudan is actually rural, such as farmers and pastoralists. These communities have also been affected by the conflict as the war has disrupted their livelihoods, lifestyles, and routes of movement. However, a comparison between nomadic lifestyle, which involves voluntary movement, and conflict-induced movement is worth mentioning.

Nomads move in large numbers, often accompanied by their livestock, which can cover the area of small settlements. Like the current displaced people, the nomadic populations can also be considered moving pieces of land. Pastoralists have been roaming the earth for centuries, if not millennia. They function to a large extent like a regular fixed settlement, growing and shrinking in size. They have full moving services catered to this number of people and animals, even though the type of required infrastructure for nomadism is obviously different from a settled settlement. They still have medical and environmental experts, routes of movement, housing, and governance.

Communal and customary land laws are a very complicated issue, so it would not be feasible to include them in this writing. However, the land required to house all the needs of nomads will always be there. If we take land use or the right to occupy land for certain amounts of time as a form of temporary ownership, this seasonal ownership that occurs every year for years creates boundaries of customary agreements and encroachments. The use in question and how resources are shared are some of the many originating causes of disagreements. But these frameworks also hold potential answers to current issues. Borrowing frameworks from these lifestyles can help tackle current issues of displacement. How do cities move? What could make a city on four legs? What if people continue to move? How can urban experts learn from the rural?

.jpeg)

What does a city mean? When we asked a resident of Old Haj Yousif if he considered his neighborhood to be a city, he said yes. We asked why, and he said it was because foreigners were now moving into the neighborhood. Haj Yousif was an urban village to the north of Khartoum that was absorbed by the city's urban expansion. I asked the same question to a resident of Alshigailab, another village that the city stretched into in recent years. His answer was that the changing livelihoods of the residents and the replanning of their village made it a city. Governments also have their own ways of deciding what a city is. Usually, the number of residents in one area of land is the key indicator; sometimes it is the types and scale of services, which are also determined by the population density of a particular geographical area. Services are placed to serve a specific catchment area. However, a unanimous understanding of a city is that it’s a fixed piece of land that expands, grows, and changes for various reasons, including sociopolitical changes.

The events of 2024 in Sudan are game-changing. By April 2024, exactly one year after the beginning of the war, over ten million people had been displaced, approximately a quarter of Sudan's entire population, according to IOM estimates. This is the population size of a megacity or twenty or so regular-sized cities. The use of a city as a measurement is critical here, as for cities to exist and be sustained, they require a certain level of infrastructure, capacity, governance, food production, and basic services. Over 80% of the displaced individuals are still within Sudan, integrating into other already extremely undeveloped villages, towns, and small cities. They are straining the capacity of these settlements and threatening the entire country with the largest humanitarian crisis in the world, and a critical state of food security and famine.

Now let's take a different angle and look at the same issue. The majority of the displaced population are urban residents fleeing three of the largest cities in Sudan: Khartoum, Wadi Madani, and Nyala. However, the largest population of Sudan is actually rural, such as farmers and pastoralists. These communities have also been affected by the conflict as the war has disrupted their livelihoods, lifestyles, and routes of movement. However, a comparison between nomadic lifestyle, which involves voluntary movement, and conflict-induced movement is worth mentioning.

Nomads move in large numbers, often accompanied by their livestock, which can cover the area of small settlements. Like the current displaced people, the nomadic populations can also be considered moving pieces of land. Pastoralists have been roaming the earth for centuries, if not millennia. They function to a large extent like a regular fixed settlement, growing and shrinking in size. They have full moving services catered to this number of people and animals, even though the type of required infrastructure for nomadism is obviously different from a settled settlement. They still have medical and environmental experts, routes of movement, housing, and governance.

Communal and customary land laws are a very complicated issue, so it would not be feasible to include them in this writing. However, the land required to house all the needs of nomads will always be there. If we take land use or the right to occupy land for certain amounts of time as a form of temporary ownership, this seasonal ownership that occurs every year for years creates boundaries of customary agreements and encroachments. The use in question and how resources are shared are some of the many originating causes of disagreements. But these frameworks also hold potential answers to current issues. Borrowing frameworks from these lifestyles can help tackle current issues of displacement. How do cities move? What could make a city on four legs? What if people continue to move? How can urban experts learn from the rural?

Nomadism of the sahel

Nomadism of the sahel

Sudan is part of the Sahel, a distinctive pan-African climate zone that is dry, hot, sunny and watered by seasonal rains; it lies at the northernmost extent of a band of rainfall fed by the distant Atlantic and Indian oceans. A rich variety of cultural traditions have evolved here that work with the landscape and the life it supports.

Communities living in the Sahel work with the climate. Some follow the rain to seasonal pastures where their livestock can graze. Others work with the seasonal rains to grow crops. Both are supported by the natural landscape, and both provide food and goods to exchange at the market and support local craft production.

This collection of documentary films is composed of four documentaries that show the heritage and culture of different nomadic tribes in Darfur and Kordofan, these films has been filmed and produced in 2019 as part of the Western Sudan Community Museums project WSCM which was originally intended to be showcased in 3 museums around Sudan; the Khalifa House Museum in Omdurman, Khartoum, the Sheikan Museum in Obaid, North Kordofan, and the Darfur Museum in Nyala, South Darfur. All films in this collection were produced by Mark Whatmore and Yoho Media.

Baggara Nomads

Archive stills and film of cattle herders in Sudan, also known as Baggara nomads in Kordofan and Darfur, from the Durham University archives, and filmed by Edward Gomer Bollard between 1939 and 1944. The film also shows stills taken by Gunnar Haaland in 1965.

Camel Culture, Darfur.

In this short documentary Mohammed Hussein Daw-Alnoor, a camel breeder from Nyala in Sudan's South Darfur (who is a manager at the Nyala Camel Market), explains the importance of camels in the culture of his tribe, Darfur and nomadic life in general. This video was filmed in Nyala Camel Market, 11/21/2019 By Mark Whatmore.

Life on the move; Darfur's Rezeigat Nomads.

Omda Abakkar Kharif Mattar, a community leader in the Rezeigat Tribe talks about the nomadic life in Darfur, and how nomadic tribes live with nature and animals, he describes the joys and meanings of their lifestyle. Filmed in West of Nyala, 15-20/11/2019 By Mark Whatmore.

Kababish Nomads

A group of camel nomads from the Kababish tribe filmed during their seasonal migration near the Jebel, North west of Bara, in a land covered with red sand dunes, as they were heading towards El Obeid, North Kordofan. On Feb 21. Filmed by Michael Mallinson.

-01.jpeg)

Sudan is part of the Sahel, a distinctive pan-African climate zone that is dry, hot, sunny and watered by seasonal rains; it lies at the northernmost extent of a band of rainfall fed by the distant Atlantic and Indian oceans. A rich variety of cultural traditions have evolved here that work with the landscape and the life it supports.

Communities living in the Sahel work with the climate. Some follow the rain to seasonal pastures where their livestock can graze. Others work with the seasonal rains to grow crops. Both are supported by the natural landscape, and both provide food and goods to exchange at the market and support local craft production.

This collection of documentary films is composed of four documentaries that show the heritage and culture of different nomadic tribes in Darfur and Kordofan, these films has been filmed and produced in 2019 as part of the Western Sudan Community Museums project WSCM which was originally intended to be showcased in 3 museums around Sudan; the Khalifa House Museum in Omdurman, Khartoum, the Sheikan Museum in Obaid, North Kordofan, and the Darfur Museum in Nyala, South Darfur. All films in this collection were produced by Mark Whatmore and Yoho Media.

Baggara Nomads

Archive stills and film of cattle herders in Sudan, also known as Baggara nomads in Kordofan and Darfur, from the Durham University archives, and filmed by Edward Gomer Bollard between 1939 and 1944. The film also shows stills taken by Gunnar Haaland in 1965.

Camel Culture, Darfur.

In this short documentary Mohammed Hussein Daw-Alnoor, a camel breeder from Nyala in Sudan's South Darfur (who is a manager at the Nyala Camel Market), explains the importance of camels in the culture of his tribe, Darfur and nomadic life in general. This video was filmed in Nyala Camel Market, 11/21/2019 By Mark Whatmore.

Life on the move; Darfur's Rezeigat Nomads.

Omda Abakkar Kharif Mattar, a community leader in the Rezeigat Tribe talks about the nomadic life in Darfur, and how nomadic tribes live with nature and animals, he describes the joys and meanings of their lifestyle. Filmed in West of Nyala, 15-20/11/2019 By Mark Whatmore.

Kababish Nomads

A group of camel nomads from the Kababish tribe filmed during their seasonal migration near the Jebel, North west of Bara, in a land covered with red sand dunes, as they were heading towards El Obeid, North Kordofan. On Feb 21. Filmed by Michael Mallinson.

-01.jpeg)

Sudan is part of the Sahel, a distinctive pan-African climate zone that is dry, hot, sunny and watered by seasonal rains; it lies at the northernmost extent of a band of rainfall fed by the distant Atlantic and Indian oceans. A rich variety of cultural traditions have evolved here that work with the landscape and the life it supports.

Communities living in the Sahel work with the climate. Some follow the rain to seasonal pastures where their livestock can graze. Others work with the seasonal rains to grow crops. Both are supported by the natural landscape, and both provide food and goods to exchange at the market and support local craft production.

This collection of documentary films is composed of four documentaries that show the heritage and culture of different nomadic tribes in Darfur and Kordofan, these films has been filmed and produced in 2019 as part of the Western Sudan Community Museums project WSCM which was originally intended to be showcased in 3 museums around Sudan; the Khalifa House Museum in Omdurman, Khartoum, the Sheikan Museum in Obaid, North Kordofan, and the Darfur Museum in Nyala, South Darfur. All films in this collection were produced by Mark Whatmore and Yoho Media.

Baggara Nomads

Archive stills and film of cattle herders in Sudan, also known as Baggara nomads in Kordofan and Darfur, from the Durham University archives, and filmed by Edward Gomer Bollard between 1939 and 1944. The film also shows stills taken by Gunnar Haaland in 1965.

Camel Culture, Darfur.

In this short documentary Mohammed Hussein Daw-Alnoor, a camel breeder from Nyala in Sudan's South Darfur (who is a manager at the Nyala Camel Market), explains the importance of camels in the culture of his tribe, Darfur and nomadic life in general. This video was filmed in Nyala Camel Market, 11/21/2019 By Mark Whatmore.

Life on the move; Darfur's Rezeigat Nomads.

Omda Abakkar Kharif Mattar, a community leader in the Rezeigat Tribe talks about the nomadic life in Darfur, and how nomadic tribes live with nature and animals, he describes the joys and meanings of their lifestyle. Filmed in West of Nyala, 15-20/11/2019 By Mark Whatmore.

Kababish Nomads

A group of camel nomads from the Kababish tribe filmed during their seasonal migration near the Jebel, North west of Bara, in a land covered with red sand dunes, as they were heading towards El Obeid, North Kordofan. On Feb 21. Filmed by Michael Mallinson.

-01.jpeg)

A bed

A bed

The meaning of home is something that gets contested a lot in times of war, what people leave behind and what they take with them as tokens of the homes they left can give glimpses to what really matters. A bed which is one of the most intimate parts of the house is a symbol of comfort and hospitality, being offered a bed to sleep is a common gesture in Sudanese households.

What is private and what is public also changes, as people share housing with others and sleep in public areas that others will try to treat as private.

The most common type of beds in Sudan is the Angareeb, a wood-framed low bed that is weaved by different types of materials. The Angareeb is a key element in various cultural events and rituals such as weddings and funerals, it has been part of the culture since the Bronze Age of the Kerma culture from 1750-1550 BC, where it was used to bury people at the time.

Wooden frame of a bed; bull-hoof feet from the New Kingdom, Purchased through: Sir Ernest A T Wallis Budge in 1887

The angareb is quite practical it could be used with or without a mattress, it’s light-weight and can be carried by one person, that’s why it’s rarely considered a fixed piece of furniture, beds get pulled out of the shade during the summer evenings in northern sudan to the yard so families sleep and spend the evenings in the cool air, angareb can be seen tied to the side of the truck and in shop fronts where the streets become the sleeping rooms for many travelers. In weddings homes the beds become drying racks for dishes and a surface for many uses.

Leather pillow or cushion. Hourglass-shaped with black and orange inserts on either side to expand the shape. Decorated with orange and black leather embroidery on one face.

Sudan; Darfur

Arkell, Anthony John [field collector and donor]

Cultural Affliation: Fellata Ibbe; nomad Felani; Baggara

1937

The bed is the first thing that gets assembled and then the tent is built around it in nomadic settlements, the concept of privacy is key as bed are placed in the most private part of the house, while the front side of the tent as well as the surroundings of the tent are used for other household activities. The beds are usually higher than the regular angareeb to provide more privacy, and it’s size take a dominant presence in the tent.

A group of women from the Umbararro Tribe in Niyala demonstrate how a tent is built 2020 © Zainab Gaafar

2 Photographic prints (black and white); 1. showing an array of woven baskets (kerio and omra) behind is a bed (sarir) in a tent. Umm Korara, South Darfur. 2. showing a camel palanquin and bed outside a tent.

May 1981

Photographed in: Darfur, Umm Korara

Paul Wilson notes this is one of a group of photographs taken at Umm Korara near Rajaj; camp of Shaykh Muhammad Sayara Abu Zakariyya [Rizaygat Jammala]. 1. "Centre is a 'sarir' [bed, called by Jammala 'hiddit'; by the Baggara itis called 'darangal', and by the Fellata 'darangal', 'layso' or 'fel'] It consists of strips of bamboo bound with leather, resting a foot above ground on sticks. Behind the bed by the tent canvas are a number of baskets - kerio + omra". 2. "Centre is shibriya or jifah - palanquin. In front of this is the 'sarir'/ 'darangal' bed".

See Collection File Af1981,18.1-70.

Representation of: Rizayqat

The meaning of home is something that gets contested a lot in times of war, what people leave behind and what they take with them as tokens of the homes they left can give glimpses to what really matters. A bed which is one of the most intimate parts of the house is a symbol of comfort and hospitality, being offered a bed to sleep is a common gesture in Sudanese households.

What is private and what is public also changes, as people share housing with others and sleep in public areas that others will try to treat as private.

The most common type of beds in Sudan is the Angareeb, a wood-framed low bed that is weaved by different types of materials. The Angareeb is a key element in various cultural events and rituals such as weddings and funerals, it has been part of the culture since the Bronze Age of the Kerma culture from 1750-1550 BC, where it was used to bury people at the time.

Wooden frame of a bed; bull-hoof feet from the New Kingdom, Purchased through: Sir Ernest A T Wallis Budge in 1887

The angareb is quite practical it could be used with or without a mattress, it’s light-weight and can be carried by one person, that’s why it’s rarely considered a fixed piece of furniture, beds get pulled out of the shade during the summer evenings in northern sudan to the yard so families sleep and spend the evenings in the cool air, angareb can be seen tied to the side of the truck and in shop fronts where the streets become the sleeping rooms for many travelers. In weddings homes the beds become drying racks for dishes and a surface for many uses.

Leather pillow or cushion. Hourglass-shaped with black and orange inserts on either side to expand the shape. Decorated with orange and black leather embroidery on one face.

Sudan; Darfur

Arkell, Anthony John [field collector and donor]

Cultural Affliation: Fellata Ibbe; nomad Felani; Baggara

1937

The bed is the first thing that gets assembled and then the tent is built around it in nomadic settlements, the concept of privacy is key as bed are placed in the most private part of the house, while the front side of the tent as well as the surroundings of the tent are used for other household activities. The beds are usually higher than the regular angareeb to provide more privacy, and it’s size take a dominant presence in the tent.

A group of women from the Umbararro Tribe in Niyala demonstrate how a tent is built 2020 © Zainab Gaafar

2 Photographic prints (black and white); 1. showing an array of woven baskets (kerio and omra) behind is a bed (sarir) in a tent. Umm Korara, South Darfur. 2. showing a camel palanquin and bed outside a tent.

May 1981

Photographed in: Darfur, Umm Korara

Paul Wilson notes this is one of a group of photographs taken at Umm Korara near Rajaj; camp of Shaykh Muhammad Sayara Abu Zakariyya [Rizaygat Jammala]. 1. "Centre is a 'sarir' [bed, called by Jammala 'hiddit'; by the Baggara itis called 'darangal', and by the Fellata 'darangal', 'layso' or 'fel'] It consists of strips of bamboo bound with leather, resting a foot above ground on sticks. Behind the bed by the tent canvas are a number of baskets - kerio + omra". 2. "Centre is shibriya or jifah - palanquin. In front of this is the 'sarir'/ 'darangal' bed".

See Collection File Af1981,18.1-70.

Representation of: Rizayqat

The meaning of home is something that gets contested a lot in times of war, what people leave behind and what they take with them as tokens of the homes they left can give glimpses to what really matters. A bed which is one of the most intimate parts of the house is a symbol of comfort and hospitality, being offered a bed to sleep is a common gesture in Sudanese households.

What is private and what is public also changes, as people share housing with others and sleep in public areas that others will try to treat as private.

The most common type of beds in Sudan is the Angareeb, a wood-framed low bed that is weaved by different types of materials. The Angareeb is a key element in various cultural events and rituals such as weddings and funerals, it has been part of the culture since the Bronze Age of the Kerma culture from 1750-1550 BC, where it was used to bury people at the time.

Wooden frame of a bed; bull-hoof feet from the New Kingdom, Purchased through: Sir Ernest A T Wallis Budge in 1887

The angareb is quite practical it could be used with or without a mattress, it’s light-weight and can be carried by one person, that’s why it’s rarely considered a fixed piece of furniture, beds get pulled out of the shade during the summer evenings in northern sudan to the yard so families sleep and spend the evenings in the cool air, angareb can be seen tied to the side of the truck and in shop fronts where the streets become the sleeping rooms for many travelers. In weddings homes the beds become drying racks for dishes and a surface for many uses.

Leather pillow or cushion. Hourglass-shaped with black and orange inserts on either side to expand the shape. Decorated with orange and black leather embroidery on one face.

Sudan; Darfur

Arkell, Anthony John [field collector and donor]

Cultural Affliation: Fellata Ibbe; nomad Felani; Baggara

1937

The bed is the first thing that gets assembled and then the tent is built around it in nomadic settlements, the concept of privacy is key as bed are placed in the most private part of the house, while the front side of the tent as well as the surroundings of the tent are used for other household activities. The beds are usually higher than the regular angareeb to provide more privacy, and it’s size take a dominant presence in the tent.

A group of women from the Umbararro Tribe in Niyala demonstrate how a tent is built 2020 © Zainab Gaafar

2 Photographic prints (black and white); 1. showing an array of woven baskets (kerio and omra) behind is a bed (sarir) in a tent. Umm Korara, South Darfur. 2. showing a camel palanquin and bed outside a tent.

May 1981

Photographed in: Darfur, Umm Korara

Paul Wilson notes this is one of a group of photographs taken at Umm Korara near Rajaj; camp of Shaykh Muhammad Sayara Abu Zakariyya [Rizaygat Jammala]. 1. "Centre is a 'sarir' [bed, called by Jammala 'hiddit'; by the Baggara itis called 'darangal', and by the Fellata 'darangal', 'layso' or 'fel'] It consists of strips of bamboo bound with leather, resting a foot above ground on sticks. Behind the bed by the tent canvas are a number of baskets - kerio + omra". 2. "Centre is shibriya or jifah - palanquin. In front of this is the 'sarir'/ 'darangal' bed".

See Collection File Af1981,18.1-70.

Representation of: Rizayqat

Sikka: A history of return

Sikka: A history of return

The images in this gallery are from Locale's contribution to the book Sudan Retold, among 31 Sudanese artists who tell stories from their homeland. The book was published in 2019 by Hirnkost. Edited by Larissa-Diana Fuhrmann and Khalid Albaih.

The images in this gallery are from Locale's contribution to the book Sudan Retold, among 31 Sudanese artists who tell stories from their homeland. The book was published in 2019 by Hirnkost. Edited by Larissa-Diana Fuhrmann and Khalid Albaih.

The images in this gallery are from Locale's contribution to the book Sudan Retold, among 31 Sudanese artists who tell stories from their homeland. The book was published in 2019 by Hirnkost. Edited by Larissa-Diana Fuhrmann and Khalid Albaih.

Due North

Due North

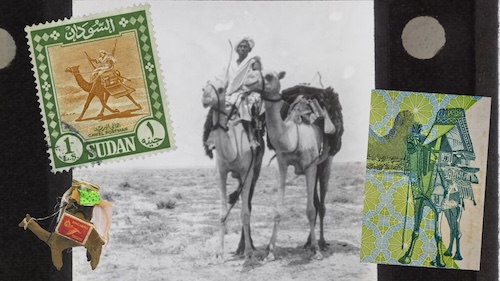

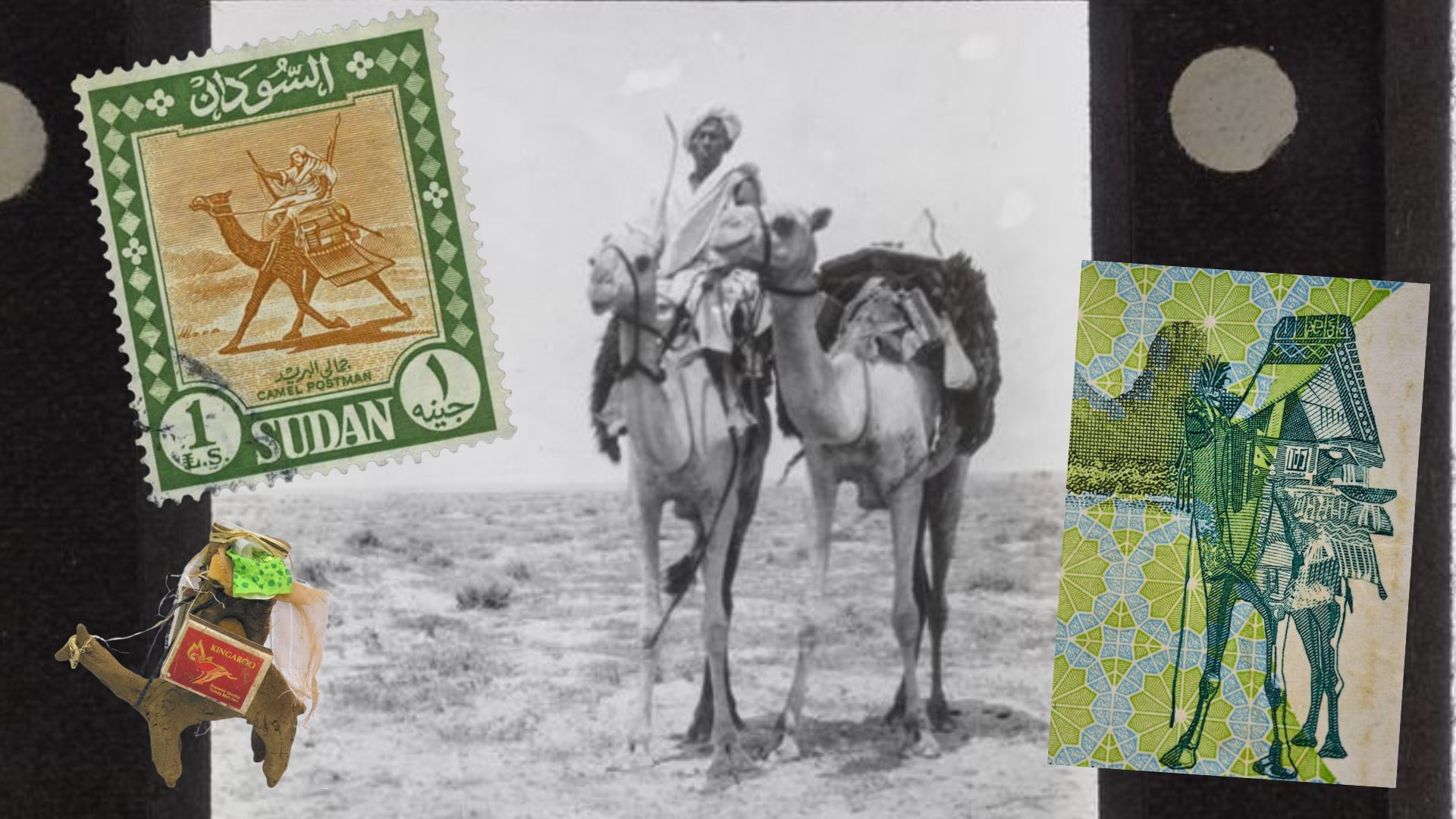

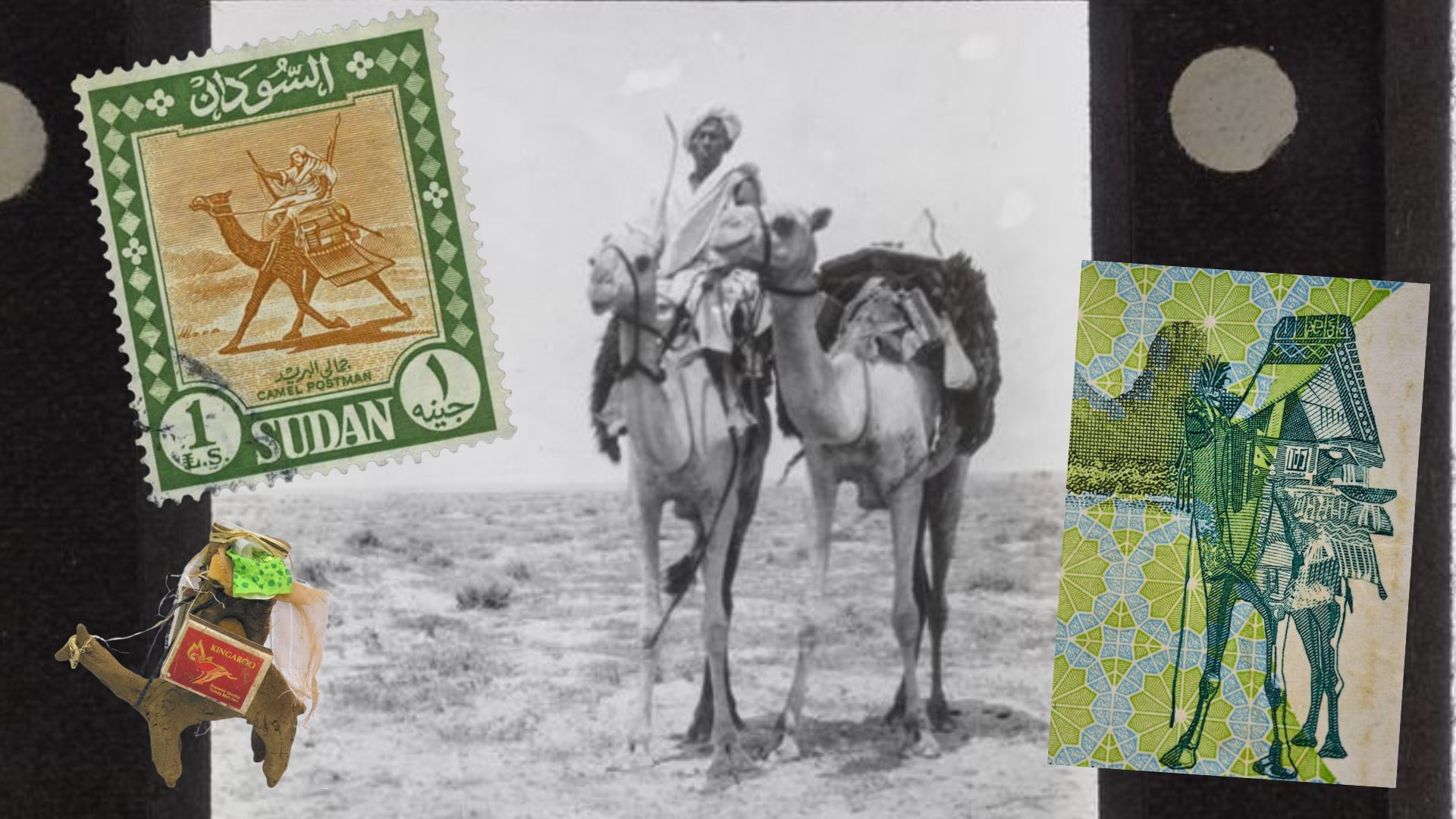

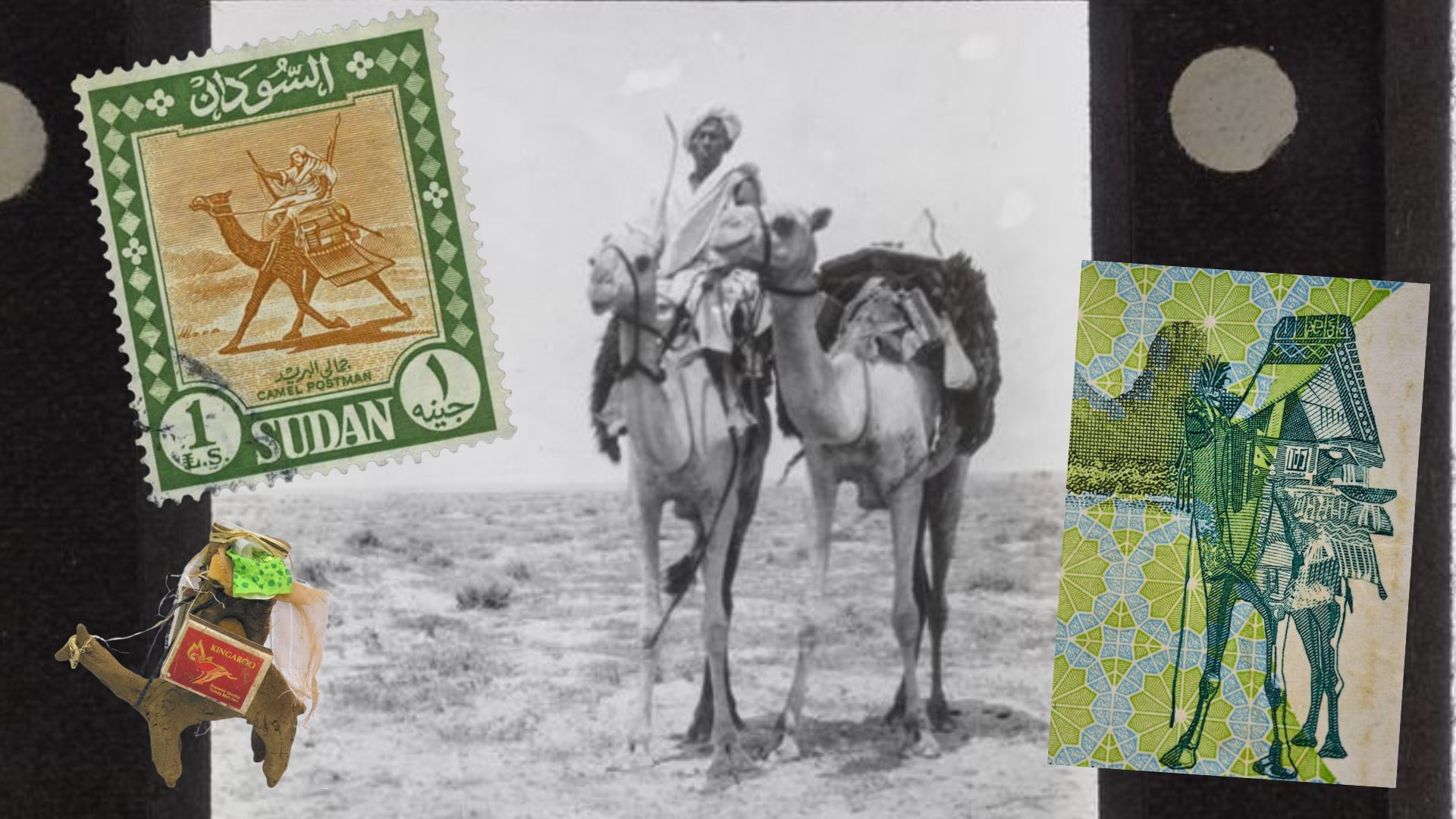

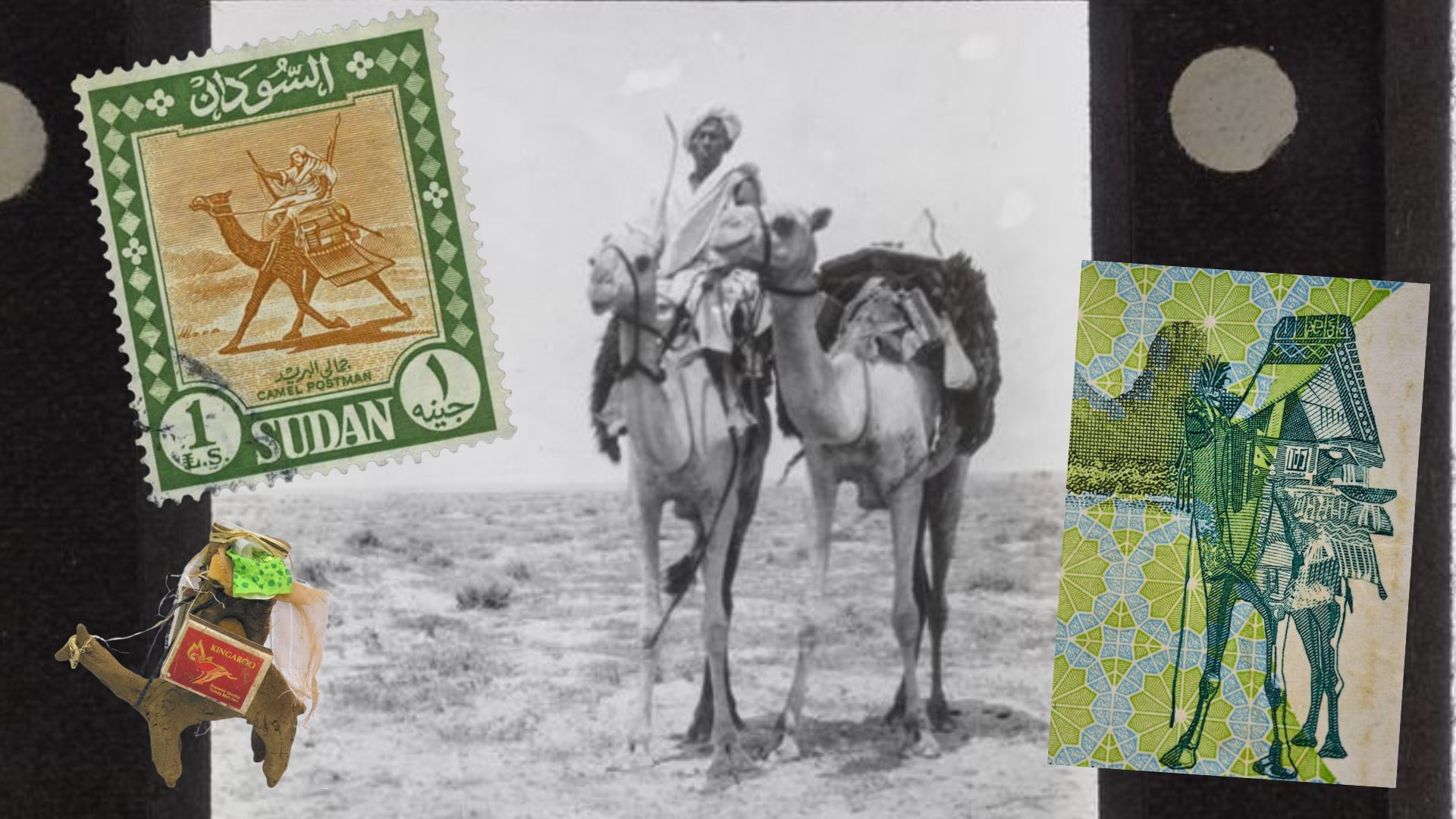

Several years ago, my father was invited by our distant relatives to join them on a unique journey from Sudan to Egypt. This would have been an unremarkable invitation if it hadn’t been for the fact that this journey was on land, through miles of arid desert, on camel back, on a route that has been used for several centuries. The invitation was to accompany the last camel caravan that our tribe the Garareesh would take to the Daraw camel market in Egypt by land through the desert, as a new road had been completed and any future trips would be taken on lorries.

Travel in all its forms is a tradition as old as time itself. Humans have been on the move forever: for food, for shelter, for safety, for exploration, and for pilgrimage. Sometimes they return to their original homes, often home is wherever they put their heads down to rest. Sometimes home is what they are searching for in the first place. This movement could be voluntary, in search of greener pastures, new relationships and economic opportunities. Or it could be forced, fleeing violence or drought, or bound into slavery to be sold. It could be on foot, on animal or on vehicles. Regardless of form or reason, it always holds one thing in common: the expectation – or fear – of something new. Sudan is no different, and its unique location as a gateway to Africa and a bridge to Mecca and Egypt has made it a busy crossroads for centuries. The camel caravans were and continue to be an inseparable part of this fabric, transporting and being transported to different destinations along routes that have been imprinted into the memory of the land and its people.

The magnificence of the camel– a wondrous creation built for the desert – is not limited to its function as a ‘vehicle of the desert’, although this function is no ordinary one. The animal has an unmatched adaptability to the harsh, hot, dry conditions, the ability to go without water or food for up to three weeks, its steady, unfaltering stride for hours on end, and its ability to carry loads many times more than other beasts of labour.

Camels are also favoured for their different products; camel meat is a popular dietary choice in many countries especially Egypt, the hide is exported to Europe to make leather products of the highest quality, and the bones are used to refine sugar, to name just a few. Some camel products are known for their near-mythical healing powers, mostly in their milk, but also strangely in their urine. As a young physician practicing in the Gulf, I witnessed this curious phenomenon first-hand.

A Bedouin baby was diagnosed with infantile leukemia in the hospital I was working in, but her family refused to let her receive any kind of medical treatment. She was brought to the hospital only when she had a fever or diarrhoea. Her diagnosis was confirmed more than once with a bone marrow aspiration – an uncomfortable procedure where a sample is taken from the marrow of the hip bone to give a picture of what blood cells are being produced and in what number. On a follow up visit and repeated test, we were shocked to find that the bone marrow contained no cancerous white blood cells at all. Which was virtually impossible because leukemia doesn’t just disappear. They told us they were giving her a small bottle of camel urine every morning.

Indeed, on more than one follow-up visit, repeated tests showed the same thing: no blood cancer cells. It appeared that the camel urine had some kind of corticosteroid effect that suppressed their production, or maybe even killed them. This effect proved to be temporary, however, and the little girl suffered from a vicious flareup of her illness and sadly passed away two months after her first birthday.

Camel routes between Sudan and Egypt

Desert routes have long been the economic lifeline between Egypt and Sudan, and from Sudan to the rest of Africa. For all its might, the River Nile has played a role of little importance in the context of trade between the two countries it links together, mainly due to the presence of six cataracts that impede movement necessary for trade. Rather, the Nile facilitated the movement of invaders over the years, carrying steamboats of missionaries and soldiers, the most famous of which was the failed expedition sent to rescue Charles Gordon. The desert routes were and continue to be an irreplaceable line along which goods, currency, culture and relationships travel back and forth between Sudan and Egypt, and through which the cultural effect of Sudan on Egypt is evident.

The routes follow the water, crossing the desert along strings of wells scattered in different directions. The three main routes the camel caravans have taken over the centuries between Sudan and Egypt are the Ababda and the Almiheila Routes for caravans coming from the east, and the Way of The Forty for those coming from the west. The biggest route is the Ababda Route named after the Ababda tribe, and dates back to the Funj Dynasty. It originates from Hussein Khalifa Basha’s palace in Eldamar in what is now the River Nile State, and passes through Korosko to Aswan to the Daraw Market in Egypt. This route was great importance for the area and for the different governments of Sudan.

The second route is the Almiheila Route from Alkasinger in the Northern State to Dalgo and has eight wells along the way. The third route is the Way of The Forty or Darb Al Arba’en, with caravans mostly from the Kababeesh tribes of Darfur in the west of Sudan and takes forty days from origin to destination. The Way of the Forty is thought to be named not just for its duration, but also for the number of trips different dervishes had taken along it, and the miracles they were thought to have performed along the way such as crossing the entire length of it on foot.

Up until 1895 there was a fourth route for the camel caravans: the now-extinct Madinab Route, named after the Madinab tribe, who used to travel in enormous caravans of up to two thousand camels to Egypt. Their route was unique in that it had no water wells at all and would have been impossible to take if it weren’t for the tribe’s use of special leather pouches impermeable to water, which they would bury deep in the desert along the way to Egypt, and dig up on the way back. The Madinab, who were famous for their integrity and honesty in trade, were completely wiped out in the Mahdiya wars, taking their caravan secrets with them.

Camel are bought from different tribes and camel markets and grouped together in caravans of growing number, with each group of camels marked with a specific mark that shows who it belongs it. If the camel should die on the way to Egypt, this mark and the bit of skin it is on it cut out and brought back to the owner as proof. The trek through the desert is a difficult one both for the animals and their riders, and not everyone lives to see the end of it. The team accompanying the caravan is made up of seasoned men with a guide familiar with the desert and its dangers, who knows where to find the wells and where to avoid snakes, scorpions and quick-sand.

The caravans travel in groups of up to one hundred camels at a time with a space of two or three days between each batch, as the capacity of the desert wells is limited and can support only so many at a time. They enter Egypt through Aswan and are met at the veterinary centers in Daraw were the camels are inspected and tagged, then loaded onto open-roofed trains to be transported the markets for sale. On the way to Egypt the riders stock up on traditional and Western medicines for themselves and the animals, non-perishable foods and matches, razor blades and needles, and tea and sugar. They arm themselves with rifles for protection from robbers lurking in the dunes. Contraband runners traveling the back routes also carried rifles but smuggled them into Egypt where weapon licenses are difficult to obtain, and smuggled back bullets into Sudan where ammunition can only be purchased through licensed stores. Caravans traveling legally bring back clothes, Egyptian cologne and perfumed soap, water pumps and filters, and molasses and sugar back to Sudan.

Gateway Between East and West

Camel caravans also transport people, livestock and merchandise from the different landlocked countries of Africa through Sudan to the Red Sea. The historic port of Suakin, a main port since as far back as the 10th century, used to be the main gateway between Africa and the East particularly for Muslim pilgrims heading to Mecca, for merchants on both side of the Red Sea, and between Africa and Europe after the Suez Canal was built. Until it was replaced by Port Sudan in the 1920s, the island port received and dispatched hundreds of camel caravans a year. The camels arrived and left the port through different routes: south from Ethiopia, north to Egypt, and north-east to Berber. They carried all sorts of merchandise depending on their origin, the diversity reflecting the diversity of the country and people of Sudan itself: sesame seeds and oil, sorghum, gum Arabic, cotton, honey, butter, coffee, tobacco and rubber. Also, rhinocerous horn, ebony, ostrich feathers, gold, musk, tortoise and seashells, mother-of-pearl and fish. And of course, racing camels, sheep, cattle and slaves.

In Suakin, the legendary Shinnawi Palace provided boarding for the camel caravans, with hundred of rooms on the top, the camel stables on the ground floor, and the massive courtyard that could hold one hundred camels at a time for loading and offloading.

In an interesting coming-to-a-full-circle moment, the detested Turkish governors of Suakin who oversaw the trade facilitated by the camel caravans also collected the taxes, and the caravans carrying these taxes north to the government in Egypt were regularly attacked by celebrated camel-riding highway men from the nomadic Arab tribes of the North. The government showed zero tolerance or mercy to whoever dared to bother these caravans – particularly on the Ababda Route – and punished those they caught in all terrible manners such as beheading and burning alive to make them an example for others.

The camel caravans in A Mouth Full of Salt

In my novel A Mouth Full of Salt, a young man from a village in North Sudan travels with the camel caravans to Egypt on the Ababda Route, which is also the route my own relatives – the Garareesh tribe – took up until the road was built, and which my father was invited to join them on but could not due to work commitments. While the camel trade is still quite alive and kicking, changing times have dictated changing traditions. The days’ long journey is no longer trekked through the desert. Instead, camels are now loaded onto lorries and driven along the new road to Egypt through the Argeen border. This trip takes just eight hours from Dongola to the Daraw market. The camels and their carers arrive a little dusty but otherwise in full strength and luster. Camels are still exported in the thousands not only for their meat and other products, but also for camel racing and beauty pageants.

The camel train made its way into my novel in bits and pieces. The camel trade with all its glory and income does not exist everywhere in Sudan. Even in the Northern State only specific areas and tribes still hold onto this tradition and are able to breed camels and trade in them. Camels are not easy beings to be tamed and dominated, and some breeds are known for their ferocity. There are all sorts of stories about what goes in the mind of a camel concerning humans they deem undesirable. I will always remember a story I was told about a herder who beat and insulted his camel, and when they were out in the desert when night, the camel (allegedly) waited until everyone was asleep then quietly moved over to wear the man was and sat on him. I find it a little troubling that after everything I learned about camels, I am still unable to tell if this story was true or made up.

This article was written with the valuable expertise and experience of Prof. Abdelrahim M Salih, professor of Anthropology and Linguistics at American University

Several years ago, my father was invited by our distant relatives to join them on a unique journey from Sudan to Egypt. This would have been an unremarkable invitation if it hadn’t been for the fact that this journey was on land, through miles of arid desert, on camel back, on a route that has been used for several centuries. The invitation was to accompany the last camel caravan that our tribe the Garareesh would take to the Daraw camel market in Egypt by land through the desert, as a new road had been completed and any future trips would be taken on lorries.

Travel in all its forms is a tradition as old as time itself. Humans have been on the move forever: for food, for shelter, for safety, for exploration, and for pilgrimage. Sometimes they return to their original homes, often home is wherever they put their heads down to rest. Sometimes home is what they are searching for in the first place. This movement could be voluntary, in search of greener pastures, new relationships and economic opportunities. Or it could be forced, fleeing violence or drought, or bound into slavery to be sold. It could be on foot, on animal or on vehicles. Regardless of form or reason, it always holds one thing in common: the expectation – or fear – of something new. Sudan is no different, and its unique location as a gateway to Africa and a bridge to Mecca and Egypt has made it a busy crossroads for centuries. The camel caravans were and continue to be an inseparable part of this fabric, transporting and being transported to different destinations along routes that have been imprinted into the memory of the land and its people.

The magnificence of the camel– a wondrous creation built for the desert – is not limited to its function as a ‘vehicle of the desert’, although this function is no ordinary one. The animal has an unmatched adaptability to the harsh, hot, dry conditions, the ability to go without water or food for up to three weeks, its steady, unfaltering stride for hours on end, and its ability to carry loads many times more than other beasts of labour.

Camels are also favoured for their different products; camel meat is a popular dietary choice in many countries especially Egypt, the hide is exported to Europe to make leather products of the highest quality, and the bones are used to refine sugar, to name just a few. Some camel products are known for their near-mythical healing powers, mostly in their milk, but also strangely in their urine. As a young physician practicing in the Gulf, I witnessed this curious phenomenon first-hand.

A Bedouin baby was diagnosed with infantile leukemia in the hospital I was working in, but her family refused to let her receive any kind of medical treatment. She was brought to the hospital only when she had a fever or diarrhoea. Her diagnosis was confirmed more than once with a bone marrow aspiration – an uncomfortable procedure where a sample is taken from the marrow of the hip bone to give a picture of what blood cells are being produced and in what number. On a follow up visit and repeated test, we were shocked to find that the bone marrow contained no cancerous white blood cells at all. Which was virtually impossible because leukemia doesn’t just disappear. They told us they were giving her a small bottle of camel urine every morning.

Indeed, on more than one follow-up visit, repeated tests showed the same thing: no blood cancer cells. It appeared that the camel urine had some kind of corticosteroid effect that suppressed their production, or maybe even killed them. This effect proved to be temporary, however, and the little girl suffered from a vicious flareup of her illness and sadly passed away two months after her first birthday.

Camel routes between Sudan and Egypt

Desert routes have long been the economic lifeline between Egypt and Sudan, and from Sudan to the rest of Africa. For all its might, the River Nile has played a role of little importance in the context of trade between the two countries it links together, mainly due to the presence of six cataracts that impede movement necessary for trade. Rather, the Nile facilitated the movement of invaders over the years, carrying steamboats of missionaries and soldiers, the most famous of which was the failed expedition sent to rescue Charles Gordon. The desert routes were and continue to be an irreplaceable line along which goods, currency, culture and relationships travel back and forth between Sudan and Egypt, and through which the cultural effect of Sudan on Egypt is evident.

The routes follow the water, crossing the desert along strings of wells scattered in different directions. The three main routes the camel caravans have taken over the centuries between Sudan and Egypt are the Ababda and the Almiheila Routes for caravans coming from the east, and the Way of The Forty for those coming from the west. The biggest route is the Ababda Route named after the Ababda tribe, and dates back to the Funj Dynasty. It originates from Hussein Khalifa Basha’s palace in Eldamar in what is now the River Nile State, and passes through Korosko to Aswan to the Daraw Market in Egypt. This route was great importance for the area and for the different governments of Sudan.

The second route is the Almiheila Route from Alkasinger in the Northern State to Dalgo and has eight wells along the way. The third route is the Way of The Forty or Darb Al Arba’en, with caravans mostly from the Kababeesh tribes of Darfur in the west of Sudan and takes forty days from origin to destination. The Way of the Forty is thought to be named not just for its duration, but also for the number of trips different dervishes had taken along it, and the miracles they were thought to have performed along the way such as crossing the entire length of it on foot.

Up until 1895 there was a fourth route for the camel caravans: the now-extinct Madinab Route, named after the Madinab tribe, who used to travel in enormous caravans of up to two thousand camels to Egypt. Their route was unique in that it had no water wells at all and would have been impossible to take if it weren’t for the tribe’s use of special leather pouches impermeable to water, which they would bury deep in the desert along the way to Egypt, and dig up on the way back. The Madinab, who were famous for their integrity and honesty in trade, were completely wiped out in the Mahdiya wars, taking their caravan secrets with them.

Camel are bought from different tribes and camel markets and grouped together in caravans of growing number, with each group of camels marked with a specific mark that shows who it belongs it. If the camel should die on the way to Egypt, this mark and the bit of skin it is on it cut out and brought back to the owner as proof. The trek through the desert is a difficult one both for the animals and their riders, and not everyone lives to see the end of it. The team accompanying the caravan is made up of seasoned men with a guide familiar with the desert and its dangers, who knows where to find the wells and where to avoid snakes, scorpions and quick-sand.

The caravans travel in groups of up to one hundred camels at a time with a space of two or three days between each batch, as the capacity of the desert wells is limited and can support only so many at a time. They enter Egypt through Aswan and are met at the veterinary centers in Daraw were the camels are inspected and tagged, then loaded onto open-roofed trains to be transported the markets for sale. On the way to Egypt the riders stock up on traditional and Western medicines for themselves and the animals, non-perishable foods and matches, razor blades and needles, and tea and sugar. They arm themselves with rifles for protection from robbers lurking in the dunes. Contraband runners traveling the back routes also carried rifles but smuggled them into Egypt where weapon licenses are difficult to obtain, and smuggled back bullets into Sudan where ammunition can only be purchased through licensed stores. Caravans traveling legally bring back clothes, Egyptian cologne and perfumed soap, water pumps and filters, and molasses and sugar back to Sudan.

Gateway Between East and West

Camel caravans also transport people, livestock and merchandise from the different landlocked countries of Africa through Sudan to the Red Sea. The historic port of Suakin, a main port since as far back as the 10th century, used to be the main gateway between Africa and the East particularly for Muslim pilgrims heading to Mecca, for merchants on both side of the Red Sea, and between Africa and Europe after the Suez Canal was built. Until it was replaced by Port Sudan in the 1920s, the island port received and dispatched hundreds of camel caravans a year. The camels arrived and left the port through different routes: south from Ethiopia, north to Egypt, and north-east to Berber. They carried all sorts of merchandise depending on their origin, the diversity reflecting the diversity of the country and people of Sudan itself: sesame seeds and oil, sorghum, gum Arabic, cotton, honey, butter, coffee, tobacco and rubber. Also, rhinocerous horn, ebony, ostrich feathers, gold, musk, tortoise and seashells, mother-of-pearl and fish. And of course, racing camels, sheep, cattle and slaves.

In Suakin, the legendary Shinnawi Palace provided boarding for the camel caravans, with hundred of rooms on the top, the camel stables on the ground floor, and the massive courtyard that could hold one hundred camels at a time for loading and offloading.

In an interesting coming-to-a-full-circle moment, the detested Turkish governors of Suakin who oversaw the trade facilitated by the camel caravans also collected the taxes, and the caravans carrying these taxes north to the government in Egypt were regularly attacked by celebrated camel-riding highway men from the nomadic Arab tribes of the North. The government showed zero tolerance or mercy to whoever dared to bother these caravans – particularly on the Ababda Route – and punished those they caught in all terrible manners such as beheading and burning alive to make them an example for others.

The camel caravans in A Mouth Full of Salt

In my novel A Mouth Full of Salt, a young man from a village in North Sudan travels with the camel caravans to Egypt on the Ababda Route, which is also the route my own relatives – the Garareesh tribe – took up until the road was built, and which my father was invited to join them on but could not due to work commitments. While the camel trade is still quite alive and kicking, changing times have dictated changing traditions. The days’ long journey is no longer trekked through the desert. Instead, camels are now loaded onto lorries and driven along the new road to Egypt through the Argeen border. This trip takes just eight hours from Dongola to the Daraw market. The camels and their carers arrive a little dusty but otherwise in full strength and luster. Camels are still exported in the thousands not only for their meat and other products, but also for camel racing and beauty pageants.

The camel train made its way into my novel in bits and pieces. The camel trade with all its glory and income does not exist everywhere in Sudan. Even in the Northern State only specific areas and tribes still hold onto this tradition and are able to breed camels and trade in them. Camels are not easy beings to be tamed and dominated, and some breeds are known for their ferocity. There are all sorts of stories about what goes in the mind of a camel concerning humans they deem undesirable. I will always remember a story I was told about a herder who beat and insulted his camel, and when they were out in the desert when night, the camel (allegedly) waited until everyone was asleep then quietly moved over to wear the man was and sat on him. I find it a little troubling that after everything I learned about camels, I am still unable to tell if this story was true or made up.